European Impressionism - The Japanese legacy

Madame Monet en costume Japonais│via Wikimedia Commons│Claude Monet

Impressionism is undoubtedly one of the most well-known and appreciated European art movements among the general public. The names of its leading figures have become so iconic that they need no introduction. Born in France at the end of the 19th century, this movement redefined the conventions of traditional painting by focusing on the capture of light, fleeting impressions, and ephemeral moments. Abandoning meticulous detail and sharp contours, Impressionist painters favored quick, visible brushstrokes of color, often applied outdoors, to suggest form and atmosphere rather than to freeze them in place.

At the time, this approach stood in stark contrast to academic conventions that prioritized precision, subdued colors, and historical or mythological themes. Thus Impressionism emerged as a major rupture, inspiring artists across Europe: in Italy, Germany, Spain, and beyond. Today, it is recognized as a key milestone in the development of modern art.

A few people know that this innovative European movement owes much to a source of inspiration from elsewhere: Japan. The 19th century saw the rise of a cultural phenomenon in Europe known as Japonism. This movement emerged at a time when exchanges between Japan and the West were still very limited. Only the Chinese and the Dutch were allowed to trade with the island nation, which remained closed to the rest of the world under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate. This isolation ended in 1868, with the opening of Japan to new trade agreements, but it was above all the 1867 Paris World's Fair that marked a true turning point. European artists discovered a radically different aesthetic, characterized by bold compositions, unconventional perspectives, and a unique use of form and color.

In this article, we will explore in detail the decisive influence of Japanese art on Impressionism, tracing its impact through the works and artists involved. By shedding light on this artistic dialogue between East and West, we will see just how profoundly this cultural exchange helped shape a movement that would redefine the course of modern art.

When Japan Fascinated Paris - The Aesthetic Shock of the 1867 World’s Fair

Long isolated from the rest of the world under the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan still maintained some distant contact with the West. Although some European influences—particularly from Flanders—had already found their way into the works of masters like Hokusai, artistic exchanges between the two cultures remained marginal. In France, the first encounters with Japanese objects date back to the early 19th century, notably at the Bazar Bonne-Nouvelle in Paris, where a few artifacts from the Far East were displayed.

A decisive turning point came in 1858 with the signing of a trade treaty between France and Japan. Cultural exchanges intensified, paving the way for a broader discovery of Japanese art by the European elite. But it was truly the 1867 Paris World’s Fair that changed everything. For the first time, Japan participated officially, just a few years before the Meiji era. The exhibition acted as a revelation: the French public encountered a radically different aesthetic, where harmony, simplicity, and refinement supplanted the classical Western canons.

This discovery caused a shockwave. Japonism was born out of this wonder and spread over the following decades. Subsequent World's Fairs—in 1878, 1889, and 1900—only deepened this fascination. Each Japanese pavilion made a stronger impression, fueling a lasting, sometimes divisive, enthusiasm among critics and artists alike.

Collectors and artists were not indifferent. Figures such as Philippe Burty, Théodore Duret, and Edmond de Goncourt became passionate advocates of Japanese art. Claude Monet amassed an impressive collection of prints, which he carefully preserved at his home in Giverny. A specialized market appeared: dealers like Siegfried Bing and Hayashi Tadamasa imported rare works and fueled a genuine cultural phenomenon.

By 1889, this enthusiasm had become institutionalized with the founding of the Guimet Museum, created through a donation by industrialist Émile Guimet, a major collector of Asian art. The National Library of France also assembled a remarkable collection of Japanese prints. Japonisme was no longer a passing trend, it had become a full-fledged cultural movement, influencing not only the visual arts but also literature and the decorative arts.

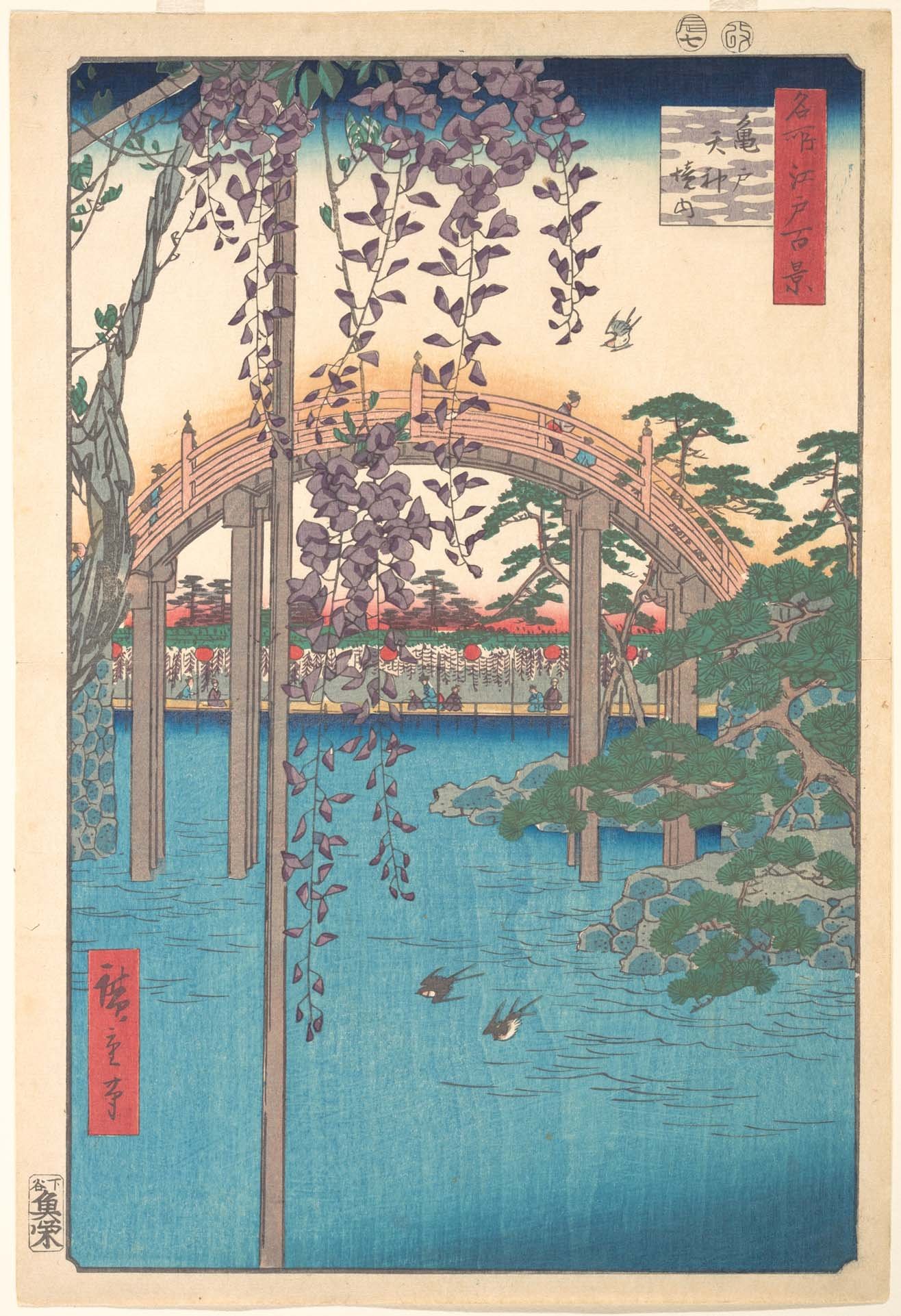

European artists, fascinated by this new visual language, adopted Japanese motifs, asymmetric compositions, and techniques. From Hokusai to Utamaro, Hiroshige to Moronobu, the masters of ukiyo-e prints exerted a lasting influence on Western production. On the eve of World War I, Japonisme had already permeated a vast portion of European artistic creation, profoundly altering the aesthetic sensibilities of the time.

When the West Appropriates Eastern Codes - Japanese Techniques in European Art

With the discovery of Japanese prints in the late 19th century, European artists underwent a true visual revolution. Far from rigid academic rules and classical compositions, Japanese art—especially ukiyo-e, or "pictures of the floating world"—offered a new way of seeing, depicting, and feeling. Kabuki theater scenes, stylized landscapes, intimate daily moments, female portraits, and erotic imagery: the subjects were diverse, but it was the technique that captivated artists most.

Unprecedented formats - folding screens, kakemonos, and fans

The aesthetic shock extended beyond imagery to include artistic formats. Folding screens, hanging scrolls (kakemonos), and painted fans introduced European artists to entirely new spatial organizations. Moving beyond framed canvases and rectangular formats, these supports inspired bold compositional approaches. Artists such as Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, and Paul Signac experimented with painting on fans, adorning their curved surfaces with urban or pastoral landscapes. The half-moon shape opened specifically a new creative avenue in European painting. The discovery of Japanese art, and especially prints, offered European artists new perspectives and techniques. They embraced these unique formats, folding screens, scrolls, fans, bringing new visual dynamics, including the half-moon composition, into Western art.

Coteaux de Chaponval│Camille Pissarro

Japanese Prints - Revolutionary Visual Codes

Works by Japanese masters like Hokusai, Hiroshige, and Utamaro impressed with their bold compositions, flat color planes, and the systematic use of black outlines to define forms. This stripped-down, stylized graphic language captivated a generation of artists searching for renewal.

Claude Monet drew on these influences in his famous Water Lilies series (1897–1926). In the later paintings, contours dissolve in favor of abstract fields of color, heralding the avant-garde movements of the 20th century.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, meanwhile, fully embraced the Japanese lesson in his iconic posters. In Jane Avril (1893) and At the Salon on the Rue des Moulins (1894), black outlines give striking definition to female silhouettes. The colors are bold, the shapes simplified—visual impact is immediate. This approach, inherited from ukiyo-e, marked a turning point in the history of Western printed imagery.

Au Salon de la rue des Moulins│via Wikimedia Commons│Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

A new conception of pictorial space

Beyond technical processes, the Japanese influence led European artists to completely rethink spatial perception. Traditional vanishing point perspective gave way to asymmetrical compositions, superimposed planes, and intentional empty spaces where absence became as meaningful as presence. The viewer's gaze moved differently; visual silence became part of the message. A quiet revolution with enduring effects.

By embracing Japanese aesthetics, Western art did more than acquire new tools, it underwent a profound transformation, inventing new visual languages that would lay the foundation for artistic modernity.

Japanese Imagery in Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Art

The influence of Japan on European painting extended far beyond formats and techniques. From the 1867 World’s Fair onward, Japanese art became more than an exotic curiosity, it fueled a new visual imagination that deeply resonated with the concerns of Impressionists and their successors. Three themes in particular stand out: women, nature, and daily life, all reinterpreted through the lens of a vision from the Far East.

The motif of the woman in kimono - elegance and fascination

Among the most striking images transmitted by Japanese art is that of women in kimonos: graceful, enigmatic, and elegant. The refinement of geishas, their poised demeanor, elaborate makeup, and sumptuous garments captivated European artists. Claude Monet, swept up by the craze, painted Camille Monet in Japanese Costume (1876), a portrait in which his wife, draped in a vibrant kimono, embodies an ideal of beauty and exoticism.

The fascination soon spread beyond painters. In bourgeois salons, parasols, fans, kimonos, and Japanese decorative objects became fashionable. Japonism did not remain confined to the canvas, it infiltrated lifestyles, clothing, and the staging of intimacy.

Scenes of daily life: celebrating the fleeting moment

Japanese prints did not only portray idealized figures; they also depicted simple, everyday gestures—often through scenes of bathing or rest, centered around female figures. This discreet, poetic intimacy found resonance with several Western artists, notably Mary Cassatt, a key figure in female Impressionism.

The American, based in Paris, drew direct inspiration from the works of Kitagawa Utamaro, a master of women-at-mirror scenes and quiet domestic moments. In her own paintings, Cassatt captured these suspended moments with similar graphic grace and emotional restraint, blending Japanese aesthetics with a modern Western sensibility.

Nature and flowers - a shared aesthetic

In Japanese tradition, nature is never neutral, it is filled with symbols, seasonal rhythms, and silence. Cherry blossoms, peonies, windblown grasses: each landscape element is treated with utmost delicacy. This sensibility clearly resonated with the Impressionists, whose goal was precisely to render the fleeting effects of light, weather, and time.

Once again, Claude Monet epitomized this aesthetic dialogue. At Giverny, he transformed his garden into a living tableau inspired by Japan: an arched bridge, a lily pond, exotic plants. It was there that he began his famous Water Lilies series—a monumental, contemplative work filled with water reflections, floral patches, and a drifting perception of reality—echoing the compositions of Hiroshige or Hokusai.

Far from being a passing fashion, Japonism penetrated the very themes of Western art, renewing its approach to intimacy, femininity, and nature. Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists did not simply admire Japan; but they absorbed its spirit to reinvent their own vision of the world.

Van Gogh and the Imagined Japan - A Tormented Artist’s Eastern Echo

If one artist’s work bears witness to the intense influence of Japanese art, it would be Vincent van Gogh. Although he came after the first wave of Japonism, the Dutch painter embraced it with unique, almost obsessive passion. For him, Japanese art was not just a source of admiration, it was a spiritual model, an aesthetic ideal, and a psychological refuge.

The birth of a passion

Van Gogh first encountered Japanese art in Antwerp, but it was in Paris in 1886 that his fascination turned into fervor. He visited key places of Japonism: Siegfried Bing’s Asian art gallery, and above all the famous shop of Père Tanguy, a figure beloved by the Impressionists who sold both paintings and Japanese prints.

Together with his brother Theo, Van Gogh began collecting woodblock prints by Hokusai, Hiroshige, and Utamaro. He didn’t just admire them, he studied, copied, and analyzed them. He even reproduced some, such as Hiroshige’s Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge, adopting their daring perspectives, vivid color planes, and clean lines. The influence was immediate and shaped his later vibrant, synthetic style.

A dream of Japan - Provence as Eastern mirage

In 1887, Van Gogh took a step further by exhibiting his print collection at the cabaret Le Tambourin. Soon after, in 1888, he left Paris for Arles in southern France, hoping to establish an artists’ studio inspired by the Japanese model: a "Japan of the South" bathed in light, serenity, and nature.

For Van Gogh, Provence became a mental projection. Influenced by Pierre Loti’s novel Madame Chrysanthème, he saw in it a European version of an idealized Japan. His blooming orchards, the famous Langlois Bridge, and even his ink drawings made during his internment in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence all reflect his quest for a Japanese aesthetic in the French landscape.

Beyond style, it was Van Gogh’s worldview that was most deeply touched. He saw in Japanese art a form of inner peace, harmony with nature, and a mental refuge from his anguish. In a letter written from Arles in September 1888 (Letter no. 519), he confided to Theo:

“We love Japanese art; we’ve all been influenced by it—every one of the Impressionists. We must return to it, live like the Japanese—more simply, more naturally, with a more artistic life.”

This fascination was also a conviction: in the luminous landscapes of Provence, Van Gogh believed he recognized the atmosphere of the Japan he so admired. As he wrote again:

“Sometimes I feel I’m in Japan.” (Letter to Theo, Arles, April 1888, no. 589)

Therefore, Provence became a mental territory for Van Gogh’s aesthetic quest for serenity, inspired directly by Japanese art. His “Japan of the South” was not a mere stylistic transposition, it was an existential attempt at healing through art. (Pic6)

Almond tree in bloom│via Wikimedia Commons│Vincent Van Gogh

When East Redraws the Contours of Western Art

Far more than a passing enthusiasm, Japonism profoundly redefined the aesthetic codes of Western art at the end of the 19th century. From Claude Monet to Mary Cassatt, Paul Signac to Vincent van Gogh, Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists found in Japanese art a new visual impulse that would transform their way of seeing and painting.

Bold framings, flat color planes, purified lines, a taste for everyday life and delicately observed nature, all were techniques drawn from ukiyo-e that challenged and renewed European academic conventions. But this influence was never mere imitation. By borrowing the codes of Japanese art, Western painters opened a new expressive horizon, one that laid the foundation for the birth of modernity in art.

The future Japan once sold returned as archived fantasy.