Texting in the 90's - Japan's Retro-Futuristic Phone Culture

The latter half of the 20th century was instrumental in cementing Japan as a technological superpower. From cameras to cars they were ahead of the curve in every category, however they stood out in one area in particular: Phones. Japanese phone culture has been pervasive since the late 60’s, and innovation in the industry has influenced western phone culture for decades. Japan-only phones have persisted since their invention, not only as an industry tool but also as an integral part of aesthetic groups of the 2000’s, peaking with the current day “Galapagos Phone”, or Garakei, in reference to the diversity of their function and look.

Whilst American company Motorola technically beat Japan to the punch with the invention of the mobile phone, Japan would come first in nearly every other innovation in the space, including the first phone service network, pioneered by NTT (Nippon Telegraph and Telephone) in 1979. Cellular devices were slowly introduced into Japan through the car phone, but it wouldn't be until 1985 that NTT would introduce what would be considered Japan’s first cell phone in the form of the shoulder phone, further expanding their phone service to now incorporate these new “mobile” phones.

Whilst essentially the same as a car phone in function, this three kilogram behemoth could be removed from the car and taken anywhere. Not only was it the first “mobile” phone in Japan, but it was one of the first phones worldwide to have a built-in phonebook. Japan was also at the forefront of the pager market as well with the Pocketbook.

This period in the early 80’s is when we see the first aesthetic customization come in to play with regards to phone culture, that being through phone cards. Phone cards were not a mobile phone accessory, but a pre-paid card that you could use at a payphone. They would often come with designs of pop culture icons, such as Gozilla or Klonoa, famous anime like Dragonball or Fullmetal Panic or pictures of famous Japanese idols or actresses, like Keiko Takeshita. These phone cards became collectibles, and once you had used the minutes on your card, you would store it in an album, very similar to the way that popular trading cards were kept.

The Pioneer

In the mid 90’s, NTT became DoCoMo, and with the change in brand as well as the rollout of smaller mobile phones with texting capabilities, interest in the culture was renewed once again. Pocketbooks and pagers had dominated the market in the early 90’s peaking at over 10 million units sold, when compared to the much smaller mobile phone market. This is likely due to the low price point, average rates being around 2000 Yen a month for unlimited calls and messages, however once traffic grew too large, companies had to adjust their billing plans to 30 Yen per 50 additional calls over the allotted monthly 200. For businessmen who corresponded internationally, and college age girls, this crept the price point out of reach, and with the introduction of the Personal Handyphone, or PHS in July of 1995, figures for the pocketbook started to look dire.

1997 would mark the final straw for the pocketbook market with the introduction of the Pioneer. The Pioneer DP-211SW, or J-Phone for convenience, was a drastic technological advancement that would precede the same innovations in the west by a decade. The Pioneer was not technically the first touch screen phone, at least not in the way we come to understand it today. In 1994 the IBM personal communicator was the first phone to have a touch responsive screen, however it was short-lived due to high price point and limited features. The Pioneer is a lot closer to what we understand a smartphone to be today, with touch screen, the ability to text and the first set of emoji’s on a phone.

However the most impressive feature of the phones of the late 90’s was the ability to connect to the internet starting with the Digital Mova F501i by Fujitsu. The phone had access to the i-mode, a Japanese mobile internet service. This service gave owners of the phone access to email, websites, and weather forecasts. Unfortunately, due to the touchscreen phones already high price point, and the fact you had to pay for data both sent and received on the i-mode network, it would be a couple years before portable internet connectivity would take off, i-mode usage peaking around 2008.

Flip Phones and Accessorising

By this point mobile phones were integrated across Japan, but what we now consider as phone culture would develop with the introduction of the flip phone. Due to Japan being relatively isolated from the rest of the world, their market diversity ends up being much larger with less imported goods. This leads to Galapagos Syndrome, which Japanese business school graduates would tell you occurs when an isolated strand of a global product is allowed to grow without competition with the international market.

This was the case with 3G flip phones, where their specialised features were allowed to grow and diversify across the Japanese market without pressure of succeeding internationally. Hiroshi Mikitani, CEO and founder of technology conglomerate Rakuten, believes that Galapagos Syndrome occurs mainly due to Japanese being the primary language of the workplace, and in such a work-centric culture, it conditions people to be less open to global products. Japanese companies such as Rakuten and Fast Retailing Co. are making an effort to change business practices that guarantee domestic success in favour of global success.

The flip phone itself would become an instant hit, especially with the younger generation. The aforementioned Galapagos Syndrome would allow for flip phones to become a customisable aesthetic purchase, as well as a functional one. The diversity in model, make and custom features would contribute to a boom in the phone market. By the early 2000’s flip phones could do everything a modern iPhone can do today, from accessing the internet to contactless payment and even photography. The flip phones became an integral part of Japanese life, and subsequently became indicators and accessories for expression.

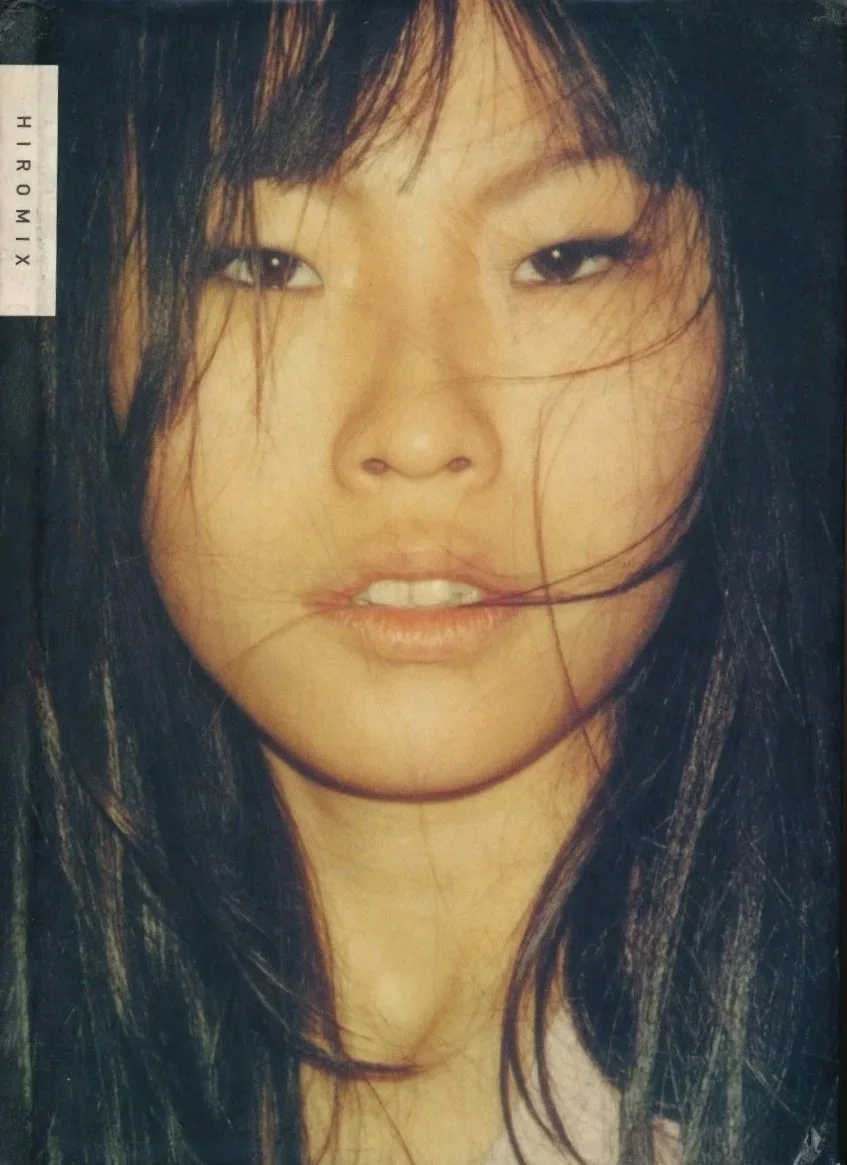

The first artist to really capitalise on this trend was a photographer called Hiromix (Hiromi Koshikawa), one of the pioneers of phone photography. Her work was incredibly influential on the young girls of Japan, so much so that she is credited for moving Japanese teenagers away from photobooths and Purikura, and helping them embrace camera-phone culture. Her photos functioned as a snapshot of Japanese youth identity and Y2K culture, and her apparatus being the flip phones front facing camera compounded these ideas.

Her collections were mostly portrait photography, with the occasional shot of urban architecture thrown in, often emphasising themes of the domestic, and foregrounding pop-culture iconography. Her incorporation of decoration and style into her portrait photography allowed her to build an identifiable world through her visual language, something that was expertly shown in “17 Girl Days”, a collection of her photos as a high school senior. Her limited technology grounded her work, allowing for an in depth and observational look at teenage identity. Whilst she started as an underground artist, she was officially recognised by Studio Voice Magazine in their article “We Love Hiromix”.

© Hiromix

The flip phone would become a key part of aesthetics like Ganguro, a subsect of Gyaru, where bulky keychains and blinged phone cases complimented the distinct and vibrant fashion trend. Toward the end of the 2000’s though the flip phone began dying out, mostly due to the advent of the smartphone. However despite its clunkier features and slower performance, the last few years have seen a resurgence in the flip phone in the younger generation. In an effort to spend less time on social media and embrace a nostalgic aesthetic, teenagers and college students have decided to pick up more modern versions of the flip phone that are able to run operating systems like Android. This embrace of an older technology retroactively proves that flip phones were never a truly functional choice, that there is something aesthetically about the flip phone that draws people in.

While f5ve draws in the world, Crystalline Structures creates their universe.