The Kid Virgil Saw

YOSHI and the shape of New Tokyo

YOSHI & Virgil│© YOSHI

There’s a reason people still talk about a 13-year-old who tied a canary-yellow Off-White™ industrial belt around his neck like a punk necktie and walked into Virgil’s Aoyama store opening. That kid was Sasaki Yoshizumi, better known as YOSHI (佐々木嘉純), born in Hiroshima Prefecture in 2003, and raised between Tokyo sidewalks and the internet’s fastest lanes. YOSHI rose at record speed from prodigy to proof-of-concept of a new hybrid path in fashion.

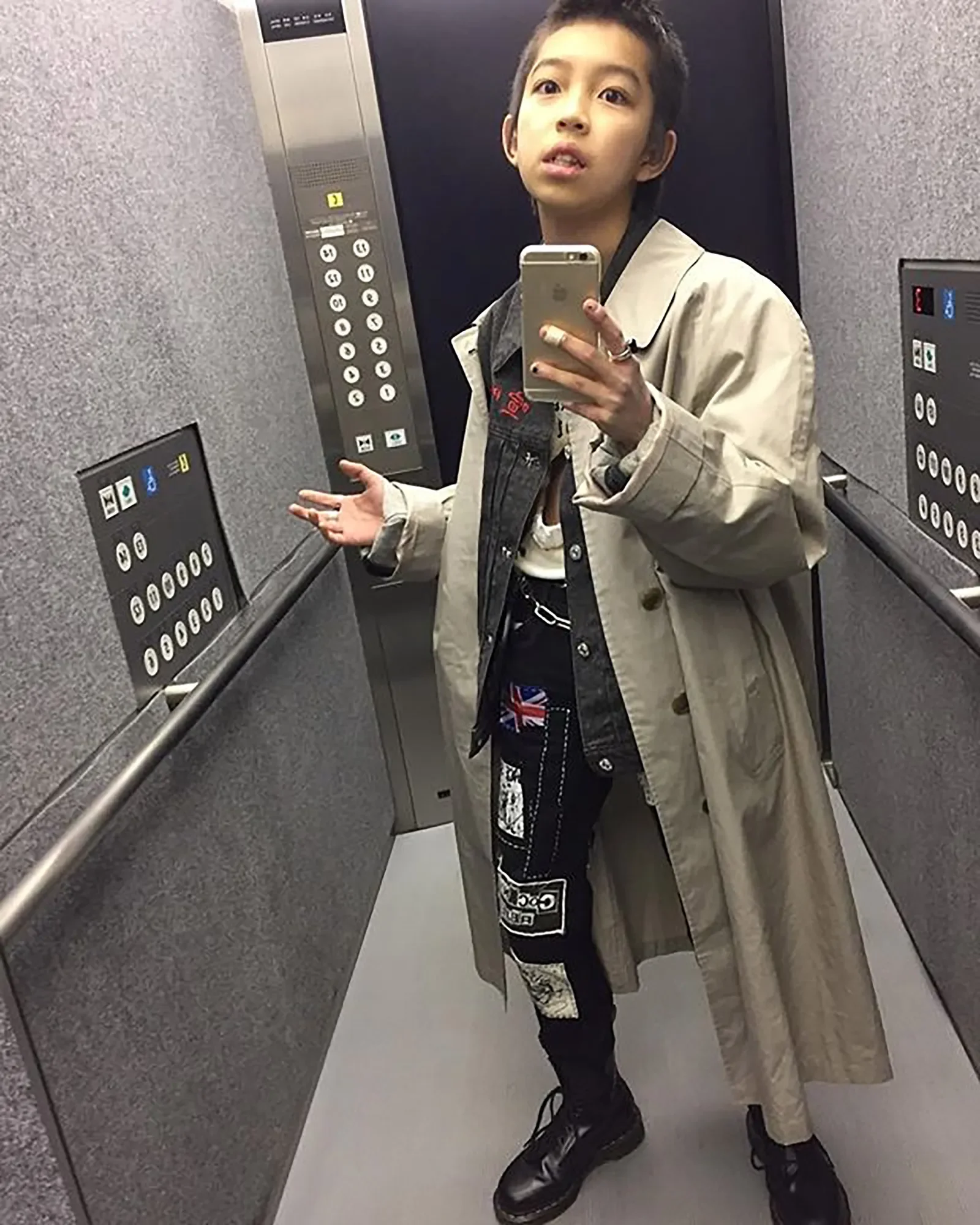

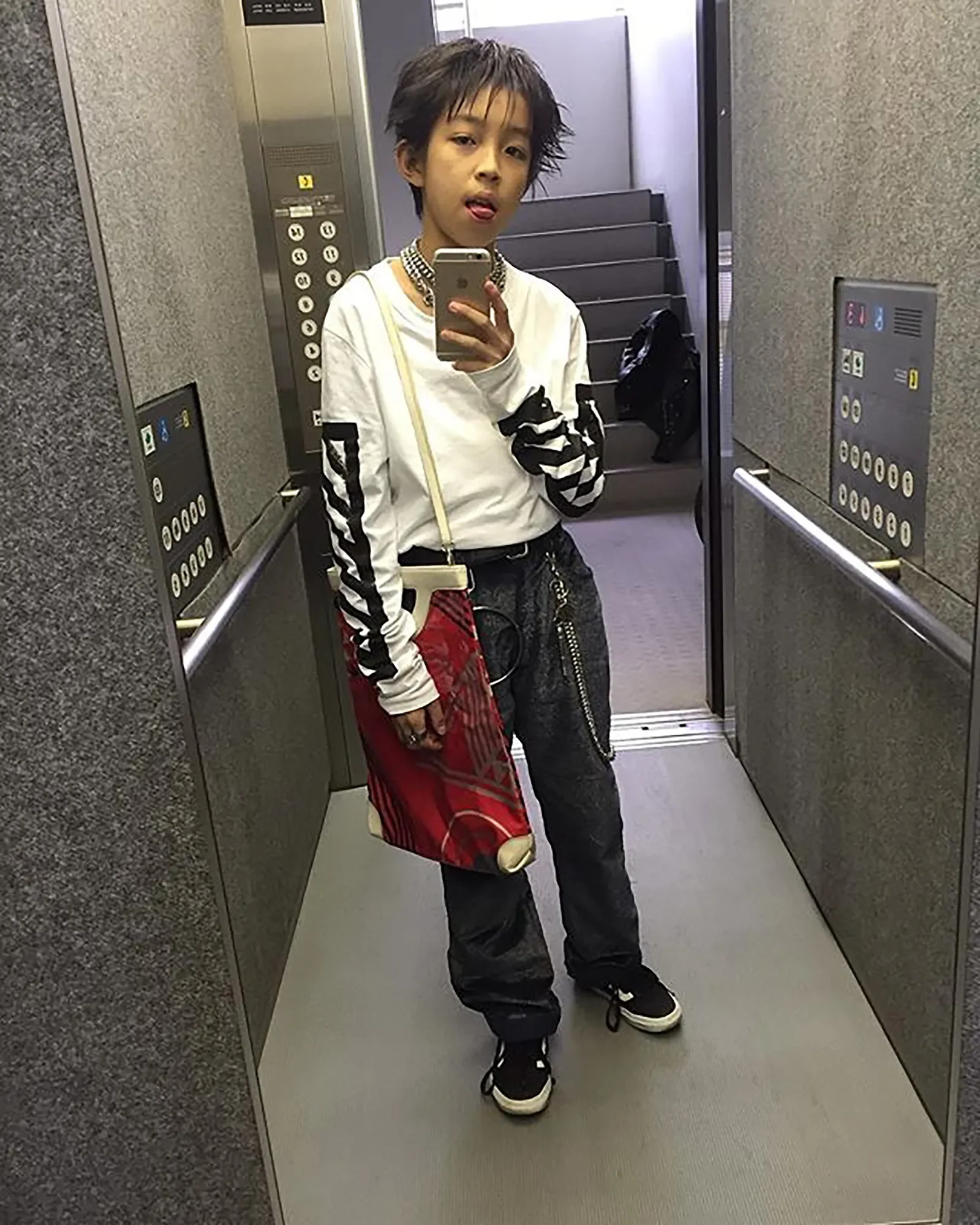

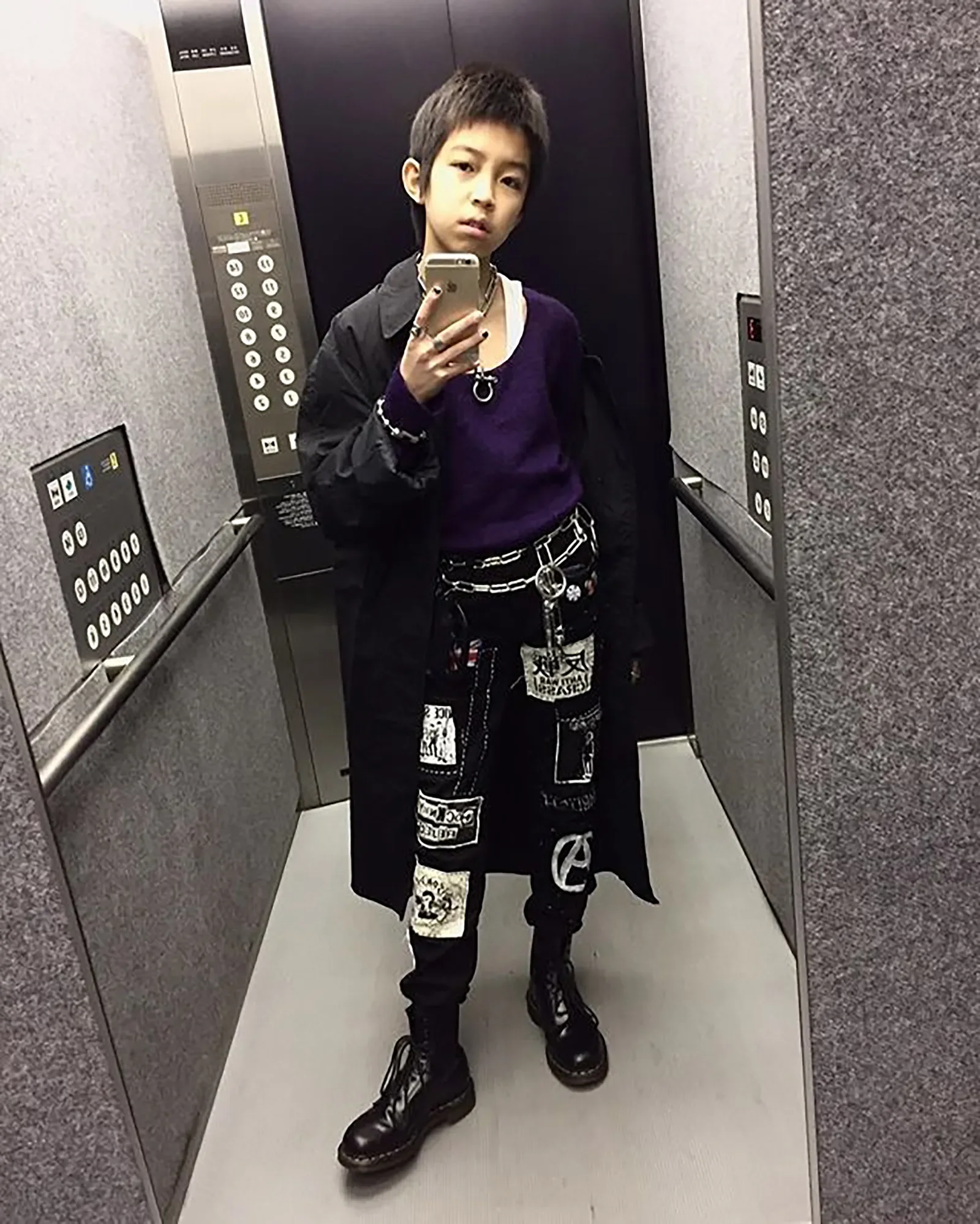

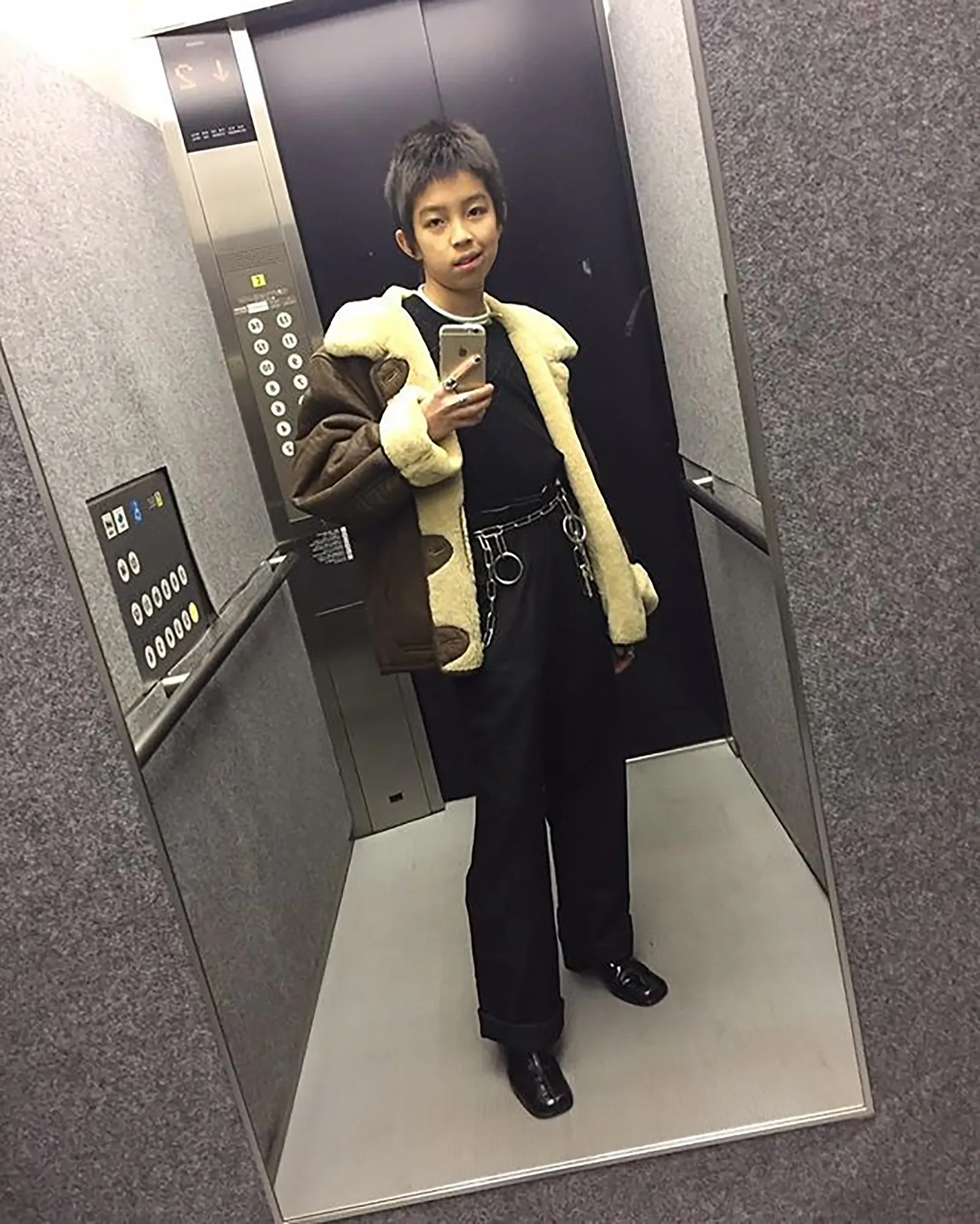

Before the casting calls and record deals came in, YOSHI learned taste the Tokyo way: at thrift stores and by watching how clothes move on the streets. He hunted at Ragtag and other secondhand spots, styled himself into a tiny lightning rod, and documented it with mirror selfies. Vogue famously crowned him the “coolest kid in Tokyo” while chronicling his Shibuya loop and the elevator-selfie habit that made him unmistakable. That same profile notes a Japanese mother and Hong Kong-born father, another clue to his borderless eye.

The hinge moment came when Virgil Abloh clocked YOSHI at the Off-White Minami-Aoyama opening. 13 years old, a belt at the neck, carrying a confident aura that said “why not?”. Abloh’s shout and a photo later, the Tokyo fashion scene had a new folk hero.

Helmut Lang and the New Casting Logic

What happened next felt inevitable in the post-Tumblr, post-GRIND era: YOSHI transitioned from street cameo to campaign face. Helmut Lang’s 2017 reboot shot by Ethan James Green, folded him into an intergenerational cast that functioned as a thesis about modern subculture that was not age-gated but more talent-forward. Press notes and coverage from the time list YOSHI alongside Alek Wek, Larry Clark, and other cult heavies, sealing his move from Tokyo micro-legend to global fashion vocabulary.

It mattered that YOSHI never dressed like a showroom model, no matter the occasion. Even when the invitations arrived, his fits always felt thrift-first and personal. His silhouettes were teen, spiky, elastic, and occasionally chaotic, but the references somehow remained always educated: leather and shearling matched against glinting boots, patched denim, a chain-lock choker, the infamous belt. YOSHI styled it so it made sense to the Harajuku lineage and to the algorithm at once.

YOSHI for Helmut Lang│© Helmut Lang

Multihyphenate, Reiwa Edition

The thing we love about Tokyo? It doesn’t ask you to pick a lane. In May 2019, at 16, YOSHI released his debut album SEX IS LIFE on Virgin/Universal; two summers later came I AM CRAZY?, hooky and punk-curious J-pop filtered through a playlist brain. The release trail is clear on Apple Music and other majors; Around the same time, Vice ran a feature that picked up on the cheeky wordplay of his lead single “Cherry Boy.”

That autumn he fronted Taro no Baka (Taro the Fool) for director Ōmori Tatsushi, a feral coming-of-age that let his rawness bloom on screen. Japanese film press and festival notes remember it as a “discovered by chance” leap, one that suddenly made his charisma legible beyond lookbooks.

What YOSHI Meant to the Subculture

Every generation in Japan gets its style emissaries. The 1990s had Ura-Harajuku shop kids and designers like Fujiwara, Takahashi, and NIGO; the 2000s had the Bunka spin-outs the likes of Chitose Abe and Hiromichi Ochiai; the late-2010s got children of resale and the omnivorous scroll. YOSHI embodied that last group’s grammar:

Vintage-first literacy. He proved that a secondhand backbone could converse with luxury without apology, a norm in Tokyo that the rest of the world still treats like revelation. See his Ragtag runs and fearless high/low splices.

Mentorship as network effect. Abloh’s open-source philosophy: remix, credit the lineage, keep the doors ajar, found a perfect student in YOSHI. The bridge Abloh later built with NIGO at Louis Vuitton (LV²) was the macro version of what YOSHI practiced micro-scale: Japanese street intuition meets global luxury codes.

Casting as culture writing. Helmut Lang’s choice to place YOSHI in a cast of cult adults reframed “cred” for the era: the kid that used to be cast because of his cute-factor suddenly was there because his styling brain already moved like a creative director’s.

YOSHI & Virgil│© YOSHI

The Ending and the Afterlives

On November 5, 2022, a motorcycle accident in Kawasaki tragically cut YOSHI’s life short at just 19. Major Japanese outlets documented the incident; in the days after, tributes poured in from music, fashion, and film. It felt unbearably abrupt, here was a voice that had been building momentum at impossible speed, suddenly gone.

And yet, YOSHI’s exceptional story refused to end there. Composer YOSHIKI revealed the two had been working together; at the family’s request he publicized a plan to complete and carry forward the music they’d started. In 2024, Shibuya PARCO hosted “YOSHI IS GOOD,” a tribute pop-up curated by STARBASE that reissued pieces YOSHI designed and channeled proceeds into causes he’d cared about. And in 2025, the documentary Rock Star of Reiwa surfaced never-before-seen footage and testimonies, aiming to fix his arc inside the decade that made him.

YOSHI wasn’t “the next Nigo” or “Abloh’s kid.” He was a prototype for a different kind of Japanese fashion actor, who treated modeling, music, and film as adjacent tabs. The through-line is how he assembled: references that collide at street level, wielding youth culture with deliberation, and refusing to let age disqualify his authority.

The grammar YOSHI wrote is still in circulation, alive each time a teenager in Harajuku ties something “wrong” and makes it look perfectly right.

Before Harajuku, Shoichi Aoki archived the world’s fashion.