Minbo - The Film That Made Its Director a Target

Minbo│© Toho

In 1992, Japanese cinema witnessed a rare act of defiance. With Minbo no Onna (The Gentle Art of Japanese Extortion), director Juzo Itami delivered a sharp, biting satire that openly mocked the yakuza, Japan’s organized crime syndicates long shrouded in an aura of intimidation and myth. The film, both a comedy and a social critique, depicted the yakuza as pathetic bullies exploiting fear to sustain their petty reigns. Just days after its release, Itami was attacked outside his Tokyo home by gang members who slashed his face, an assault widely interpreted as retaliation. Five years later, in 1997, Itami died in circumstances that remain highly suspicious, falling from the rooftop of his office building in what was officially ruled a suicide. Many, including journalists and close associates, suspect that his death was linked to his unwavering opposition to the yakuza’s influence in Japanese society.

Before Minbo, Juzo Itami had already made his mark as one of Japan’s most distinctive and socially engaged filmmakers. A former actor who appeared in over 60 films including Ozu’s Floating Weeds (1959), Itami transitioned to directing in the 1980s and quickly gained recognition for his unorthodox, irreverent style. His debut, The Funeral (Ososhiki, 1984), dissected Japanese mourning rituals with wry humor. The following year, Tampopo (1985) became an international cult hit, blending the structure of a spaghetti Western with a gourmand’s ode to ramen. Then came A Taxing Woman (Marusa no Onna, 1987), a bold critique of financial corruption and tax evasion, which won Itami the Japan Academy Prize for Best Picture and Best Director. With each film, he sharpened his gaze on Japanese institutions (customs, bureaucracy, gender roles) and turned his lens toward the absurdities and hypocrisies hidden beneath the surface of polite society.

By the early 1990s, the yakuza were undergoing a transformation. No longer confined to the shadows, they had embedded themselves in Japan’s bubble economy of the late 1980s, diversifying their operations into construction, entertainment, and real estate. Despite being technically illegal, many yakuza groups operated openly, with offices, business cards, and a coded form of legitimacy. Their public image, partly shaped by cinema itself, oscillated between brutal criminality and a stylized, even romanticized, code of honor. Within this context, Minbo was a slap in the face. It stripped away the cinematic glamour that had long surrounded these figures and portrayed them instead as pitiful extortionists preying on the weak and relying on ritualized intimidation.

As Jake Adelstein, crime journalist and author of Tokyo Vice, later wrote: “Itami’s Minbo didn’t just ridicule the yakuza, it delegitimized them. It pulled the curtain back on their tactics, revealing them as sad, thuggish remnants of a bygone era”. That exposure, combined with the film’s commercial success, made Itami a target. What followed was a chilling reminder that satire, when wielded fearlessly, can provoke not only laughter, but retaliation.

Minbo│© Toho

The Satirical Style of Minbo and Its Depiction of the Yakuza

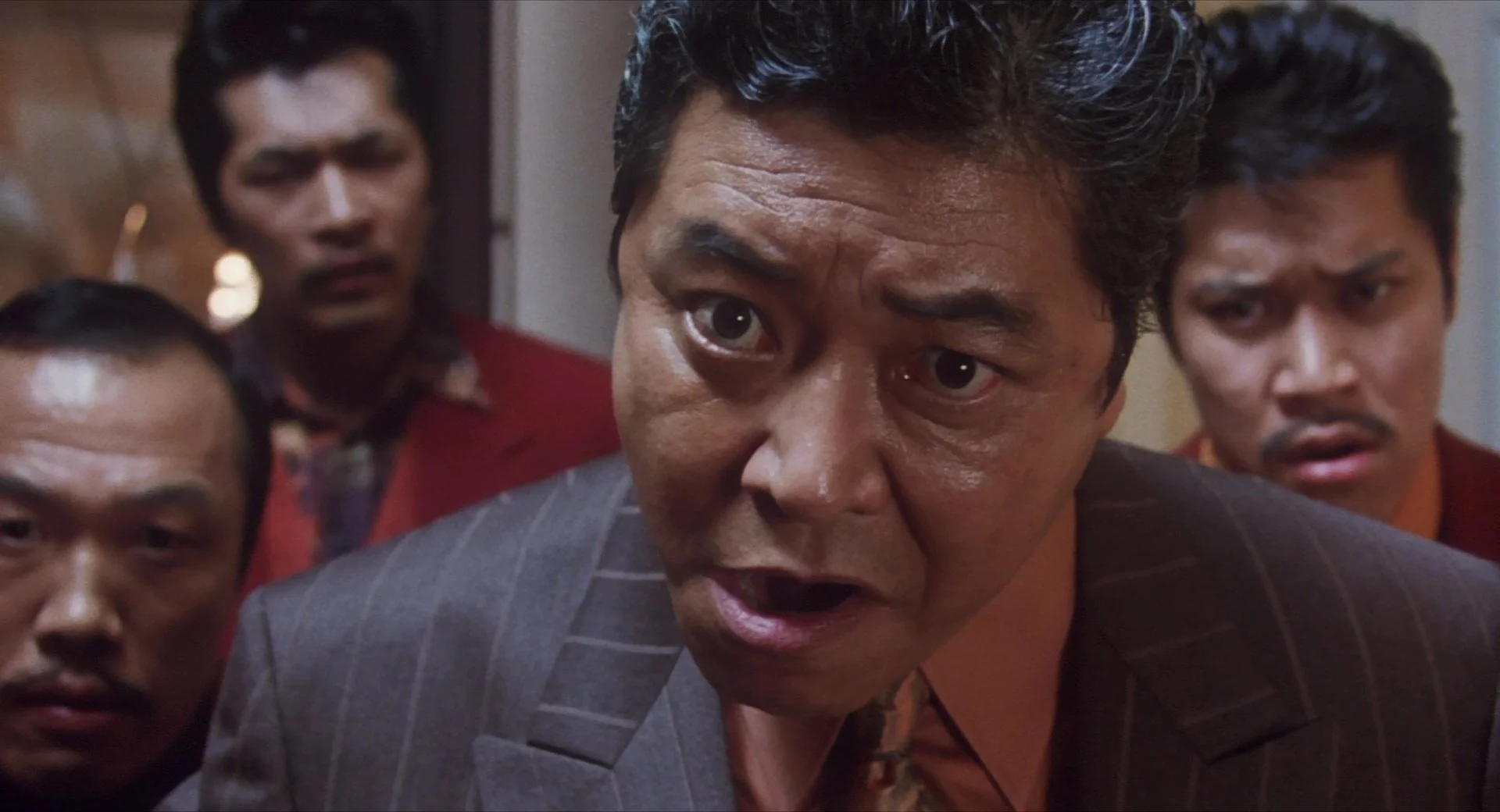

The plot of Minbo follows Mahiru Inoue, a shrewd and pragmatic lawyer (played by Nobuko Miyamoto, Itami’s wife and frequent collaborator) hired by a luxury hotel to help rid it of a group of yakuza exploiting loopholes to extort money. Through her clear-headed legal strategies and psychological defiance, she dismantles the gang’s tactics one by one, exposing their dependence on social decorum, fear-mongering, and the silence of their victims. Inoue becomes a symbol of rationality and civic courage, standing in stark contrast to the clumsy and arrogant gangsters who rely more on showmanship than violence.

The film is a true lesson in tonal balance, a social satire with comic overtones, handled with surgical precision. At the heart of the film lies a biting critique of the yakuza, but also a broader indictment of the culture of fear and passivity that allows such groups to flourish. Rather than resorting to the grim, noir aesthetics often associated with organized crime dramas, Itami opts for bright lighting, dynamic pacing, and moments of absurdity that lay bare the performative nature of power and intimidation in contemporary Japan.

Itami’s satire works by ridiculing the very foundation of yakuza power: their image. The gangsters in Minbo are not cool, dignified figures of respect, but petty manipulators in cheap suits who rely on bravado, implied threats, and social discomfort. One memorable scene sees a yakuza member feigning outrage in a hotel lobby, theatrically slapping his own face to fabricate a complaint, only to be calmly outmaneuvered by Inoue’s legal logic. The effect is disarming, and even comical, but beneath the humor lies a serious message, that yakuza’s influence persists because of a society unwilling to confront them.

The filmmaker’s satirical lens also draws on his background in advertising and media, skewering the surface-level aesthetics and polite rituals that conceal deep dysfunction. His characters are exaggerated just enough to highlight their social archetypes without devolving into caricature. The yakuza here are neither tragic villains nor misunderstood rebels, but clowns in a system that unwittingly props them up.

Minbo│© Toho

The Assault on Itami and the Media Fallout

Just days after the release of Minbo, Juzo Itami was ambushed outside his Tokyo home by five men. They beat him severely, slashing his face with a knife, breaking his nose and damaging his teeth. The attackers fled quickly, but the message was unmistakable, the film had struck too close to the truth. In mocking the yakuza, denuding them of their mystique and portraying them as petty, manipulative thugs, Itami had crossed a line rarely approached by Japanese filmmakers, and the retaliation was swift, brutal, and symbolic.

The assault shocked the public. Although violence by yakuza groups was not uncommon, such a direct and calculated attack on a high-profile cultural figure was extraordinary. Itami’s injuries, particularly the deliberate facial slashing, were reminiscent of kiri, a yakuza-style warning intended to humiliate as well as punish. The act of defacing a director who had dared to “unmask” them on screen was itself a grotesque performance, a real-life echo of the theatrical intimidation tactics depicted in the film.

According to reports later confirmed by police investigations and journalistic inquiries, the attack was orchestrated by members of the Goto-gumi, a branch of the larger Yamaguchi-gumi syndicate (Japan’s most powerful yakuza group). Itami, however, refused to be silenced. In a defiant press conference held shortly after his hospitalization, he appeared in public with his face still bandaged and declared: “They cut very slowly, they took their time. They could have killed me if they wanted”. (Source: New York Times)

Ironically, the violent response to Minbo only amplified its impact. The film saw renewed attention as the media spotlight intensified. In many ways, the assault confirmed the very thesis of his film, that the yakuza’s power depends less on strength than on fear, and that challenging them publicly is a dangerous, but necessary, act of civic defiance.

Minbo│© Toho

The Suspicious Circumstances of Itami’s Death

On December 20, 1997, Juzo Itami was found dead outside his Tokyo office building, having apparently jumped from the rooftop of the five-story structure. A suicide note, typed and unsigned, was discovered nearby, in which he reportedly confessed to being diagnosed with terminal cancer and claimed his intention to end his life before becoming a burden. The Japanese public was stunned. Itami was 64 years old, still active in the industry, and had shown no overt signs of illness or despair. Almost immediately, suspicions arose. Was this truly suicide, or had the director who defied the yakuza once too often been silenced?

The official cause of death was recorded as suicide. But questions lingered, and for many, the details didn’t add up. Friends and family noted that Itami had been in good spirits in the days leading up to his death. His brother-in-law, the novelist Kenzaburo Oe (a Nobel laureate), was among those who publicly questioned the narrative, pointing to inconsistencies in the reported circumstances. Most notably, the alleged cancer diagnosis that supposedly motivated the suicide was never confirmed by medical records. There was also the matter of the note, it lacked the distinct tone and wit that characterized Itami’s voice, and no one could verify that he had written it.

In the years following his death, persistent rumors circulated in journalistic and political circles. According to a 2008 Shukan Gendai investigation, sources within the Tokyo Metropolitan Police quietly suspected foul play but were reluctant to pursue it further, in part due to the sensitivity surrounding organized crime. The most compelling allegation emerged in 2008, when Jake Adelstein, a seasoned crime reporter and author of Tokyo Vice, cited an unnamed former yakuza member who claimed that Itami had been murdered by the Goto-gumi faction of the Yamaguchi-gumi syndicate, the same group believed to be behind the 1992 assault. According to this source, the director had been lured to the rooftop by gang members posing as reporters and was given a brutal ultimatum: jump or be pushed: “We set it up to stage his murder as a suicide. We dragged him up to the rooftop and put a gun in his face. We gave him a choice: jump and you might live or stay and we’ll blow your face off. He jumped. He didn’t live.” (Source: japansubculture.com)

The murder was allegedly staged to look like suicide in order to avoid the media fallout that a blatant assassination would provoke. “Itami was becoming too influential,” Adelstein later wrote, “and his films had caused too much embarrassment. He was a liability.” These claims, while unproven, gained traction due to the credibility of Adelstein’s reporting and the known tactics of yakuza intimidation. The Goto-gumi, in particular, had a reputation for violent retaliation against perceived enemies. Their involvement in media suppression and political corruption had long been whispered about in hushed tones, especially during the 1990s, when yakuza groups still wielded considerable social and economic influence.

More than two decades after his death, Juzo Itami remains a singular figure in Japanese cinema for his sharp and satirical filmmaking, but also for the personal risks he took in confronting the darker forces of his society. Minbo, with its biting humor and fearless critique of yakuza intimidation, exemplifies his commitment to truth-telling through art. It is a film that pierced the carefully maintained silences of post-bubble Japan and, in doing so, may have provoked consequences far beyond the screen.

While the official narrative surrounding Itami’s death remains unchallenged by the authorities, the unease lingers. The ambiguity of his final hours, combined with his history of standing up to organized crime, continues to cast a long shadow over his legacy. Yet Itami's voice endures. His films are still watched, studied, and admired for their intelligence, courage, and irreverence. Minbo is a cultural flashpoint, a symbol of resistance against fear and coercion. In a country where silence is often safer than dissent, Itami dared to laugh at the powerful, and paid the price. That legacy remains an essential part of understanding both the man and the society he so brilliantly observed.

The future Japan once sold returned as archived fantasy.