Shigeru Sugiura - Pop Surrealist of Postwar Manga

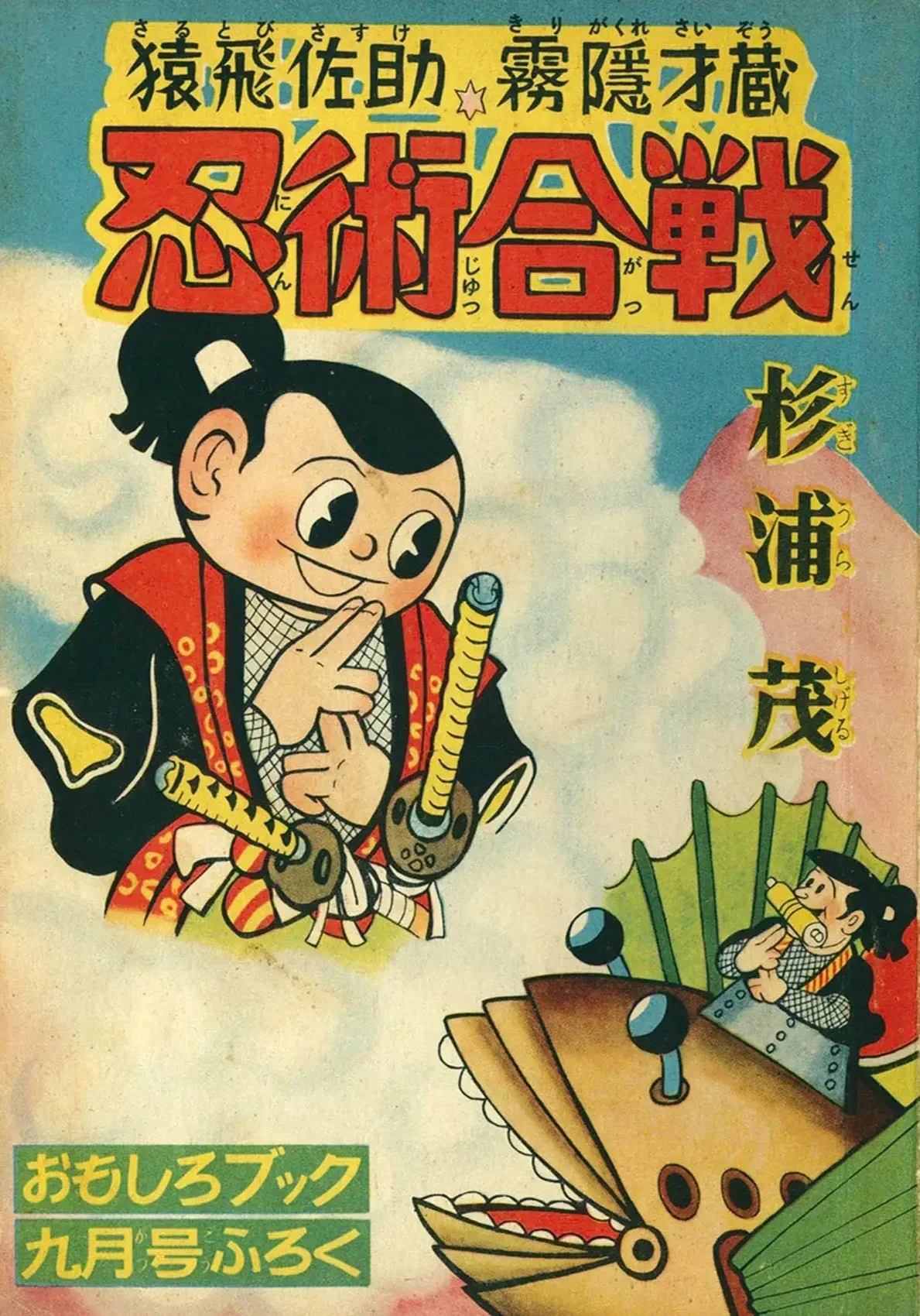

Ninjutsu Battle (1954)│Shigeru Sugiura│via Mandarake

In the crowded pantheon of postwar Japanese manga, certain names dominate the collective memory, such as Osamu Tezuka (Astro Boy), the so-called “god of manga”, Shotaro Ishinomori (Kamen Rider), and Fujiko Fujio (Doraemon). Yet lingering at the eccentric fringes of this history is Shigeru Sugiura (1908-2000), a cartoonist whose work resisted the straight lines of convention and whose influence continues to ripple through the worlds of manga, pop art, and experimental illustration. Less a household name than a cult figure, Sugiura fashioned a body of work that defied the gravity of realism, embracing instead a kaleidoscopic mix of slapstick humor, grotesque distortion, and surreal visual energy.

Born in Tokyo before manga had crystallized into the postwar industry we know today, Sugiura began his career in the 1930s as an illustrator, later flourishing in the 1940s and 1950s as part of a generation of artists who would define the medium for mass audiences. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Sugiura never confined himself to straightforward narrative or linear storytelling. His pages often read as anarchic collages, wide-eyed children and anthropomorphic animals tumbling through impossible landscapes, while pop-cultural references from samurai films to American cartoons, clash in bizarre and often subversive juxtapositions. Critics have called him a “pop surrealist” avant la lettre, a Japanese parallel to Western underground comics that would not emerge until the 1960s.

Sugiura’s work resonates for its eccentricity, but also for the way it embodied a postwar sensibility, chaotic, absurd, and playful, yet deeply critical of authority and order. His art absorbed the cultural turbulence of his time, the influx of American occupation-era media, the rapid modernization of Japan, and the tension between popular entertainment and avant-garde experimentation. In this way, his manga anticipated the later hybridity of Japanese pop culture, blurring the line between high and low, parody and sincerity.

Dense Forest and Adventure Hatch (1947)│Shigeru Sugiura│via Mandarake

From Early Career to Postwar Breakthrough

Shigeru Sugiura’s trajectory as a manga artist cannot be understood without situating him in the volatile decades that bridged prewar and postwar Japan. Born in Tokyo in 1908, Sugiura came of age during a time when manga was still fluidly defined, a hybrid between illustrated humor magazines, newspaper caricature, and children’s adventure comics. His artistic sensibility was shaped by both Japanese traditions of cartooning, stretching back to ukiyo-e caricature and early satirical prints, and the influx of foreign visual culture, particularly American comic strips and animation. Walt Disney’s elastic style, Max Fleischer’s surrealism, and the slapstick of Tex Avery were crucial points of reference, yet Sugiura processed these influences in ways that were uniquely Japanese and deeply idiosyncratic.

His professional debut came in the 1930s, when he began contributing to popular boys’ magazines, producing adventure stories infused with humor and dynamism. These early works often reflected the nationalistic currents of the era, where militarism and empire seeped into children’s culture. Like many artists of his generation, Sugiura produced war-themed illustrations during the Second World War, though his irreverent line and grotesque exaggerations already distinguished him from more orthodox propagandistic artists. Even within the strictures of censorship, Sugiura’s visual world retained a kind of absurdist elasticity, where machines, animals, and humans alike seemed to collapse and transform in unpredictable ways.

The end of the war in 1945 marked both a rupture and a rebirth for Sugiura’s career. As Japan staggered under occupation, censorship gave way to a flood of American comics, pulp magazines, and Hollywood films, all of which invigorated the young manga industry. Sugiura was quick to seize upon this changing cultural landscape. His manga from the late 1940s and early 1950s stood out for their manic pacing, outlandish gags, and surreal distortions of reality. While Osamu Tezuka was constructing grand narratives and cinematic page layouts that would define modern story manga, Sugiura leaned into parody, grotesquerie, and slapstick. His work often mocked the very seriousness that was becoming central to postwar manga’s new identity.

One of Sugiura’s best-known works from this period, Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke (1953), encapsulates this duality. On one hand, it drew on the booming popularity of ninja and samurai stories, genres that resonated with a nation rediscovering its cultural past. On the other hand, Sugiura infused the narrative with manic exaggeration. In doing so, he undermined the very tropes he employed, creating works that oscillated between homage and satire.

By the 1950s, Sugiura was a popular figure among young readers, his comics selling briskly and resonating with audiences hungry for laughter after years of war and deprivation. The artist’s postwar output embodied a kind of anarchic energy, a refusal to abide by the narrative or stylistic norms that were crystallizing around Tezuka’s model. Instead, Sugiura cultivated a style that was at once childlike and grotesque, populist and avant-garde.

Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke (1953)│Shigeru Sugiura

Surrealism, Grotesque Humor, and Pop Collage

If Shigeru Sugiura’s early postwar career established him as a popular entertainer, it was his stylistic evolution in the 1950s and 1960s that secured his reputation as one of manga’s true surrealists. One of the most striking aspects of Sugiura’s work is his use of the grotesque. His characters often veer into caricature so extreme that they become unsettling, faces distort into grimaces, bodies contort in impossible ways, and physical comedy teeters on the edge of nightmare. Sugiura’s comics operate in a “surreal-grotesque register” that destabilizes the conventions of children’s manga while still engaging their sensibilities. The result is a kind of double-coding, works that delight younger readers with slapstick antics while also offering a disturbing absurdity that appeals to more subversive tastes.

Equally important was Sugiura’s embrace of collage-like juxtapositions. His pages frequently blend traditional Japanese motifs (samurai, ninja, yokai) with imported imagery from American comics, pulp magazines, and Hollywood cinema. This layering created a unique pop collage effect, in which cultural references crashed into one another with gleeful irreverence. For example, a ninja might suddenly find himself battling a cowboy or robot, Edo-period landscapes might dissolve into slapstick chase sequences reminiscent of Tex Avery. In this sense, Sugiura anticipated the postmodern mash-up aesthetics that would later characterize global pop culture. Humor was Sugiura’s most potent weapon. But unlike Tezuka’s gentle irony, Sugiura’s comedy was manic and often absurdist. Characters frequently broke the fourth wall, mocked their own narratives, or devolved into parodic exaggeration.

By the 1960s, this unique mixture of surrealism, grotesque humor, and pop collage had begun to align Sugiura with avant-garde movements beyond manga. Artists like Yoshiharu Tsuge and Seiichi Hayashi admired Sugiura’s willingness to push against the boundaries of manga’s form, even as his reputation in mainstream publishing waned. The younger underground generation saw in his comics a precedent for their own experiments in surrealism, satire, and anti-establishment critique.

Dalchan (1974)│Shigeru Sugiura│via Mandarake

Decline, Rediscovery, and the Cult of Sugiura

Shigeru Sugiura’s flamboyant style, once a staple of rental manga shops and children’s magazines, began to lose its foothold by the late 1960s, in Japan’s rapidly evolving comics landscape. The industry was shifting towards longer, serialized narratives aimed at older readers, epitomized by gekiga artists such as Yoshihiro Tatsumi and Takao Saitou, whose gritty realism and mature themes resonated with an audience coming of age in the shadow of social upheavals and political protest. In contrast, Sugiura’s work appeared out of step with the sober tone of the times. His career declined as publishers turned away from his brand of frenetic, collage-like comedy, relegating him to the margins of an increasingly stratified manga industry.

In the 1970s, he was rediscovered by a new generation of artists, critics, and avant-garde enthusiasts who recognized in his comics a radical energy overlooked by mainstream audiences. Journals such as Garo began to treat Sugiura as a proto-surrealist whose work anticipated the heta-uma (“bad-but-good”) aesthetics. The artist’s grotesque humor and cultural mash-ups resonated with underground creators seeking to dismantle the boundaries between high and low art.

This reappraisal transformed Sugiura into a cult figure. No longer judged by the commercial standards that had marginalized him, he was instead celebrated for his visionary eccentricity. In the 1980s and 1990s, exhibitions and reprints of his work reframed his manga as a form of pop surrealism, situating him within broader global currents of avant-garde and underground art. Art critics began to compare his grotesque parodies and frenetic collages to the sensibilities of European surrealists and American underground cartoonists. To admirers, his work no longer seemed outdated, but rather prophetic, anticipating the postmodern mash-up aesthetics that would dominate global culture by the end of the century.

At once a popular entertainer and a proto-avant-garde visionary, he built a body of work that mirrored the kaleidoscope of postwar Japanese culture. By weaving together contemporary fads, he created manga that delighted in yukai, the philosophy of amusement and bodily freedom, pushing his characters into absurdist extremes of movement and transformation. What began as slapstick for mass audiences gradually evolved into a surreal and experimental visual language, especially as the demands of weekly serialization left him unable, or unwilling, to conform to industrial production.

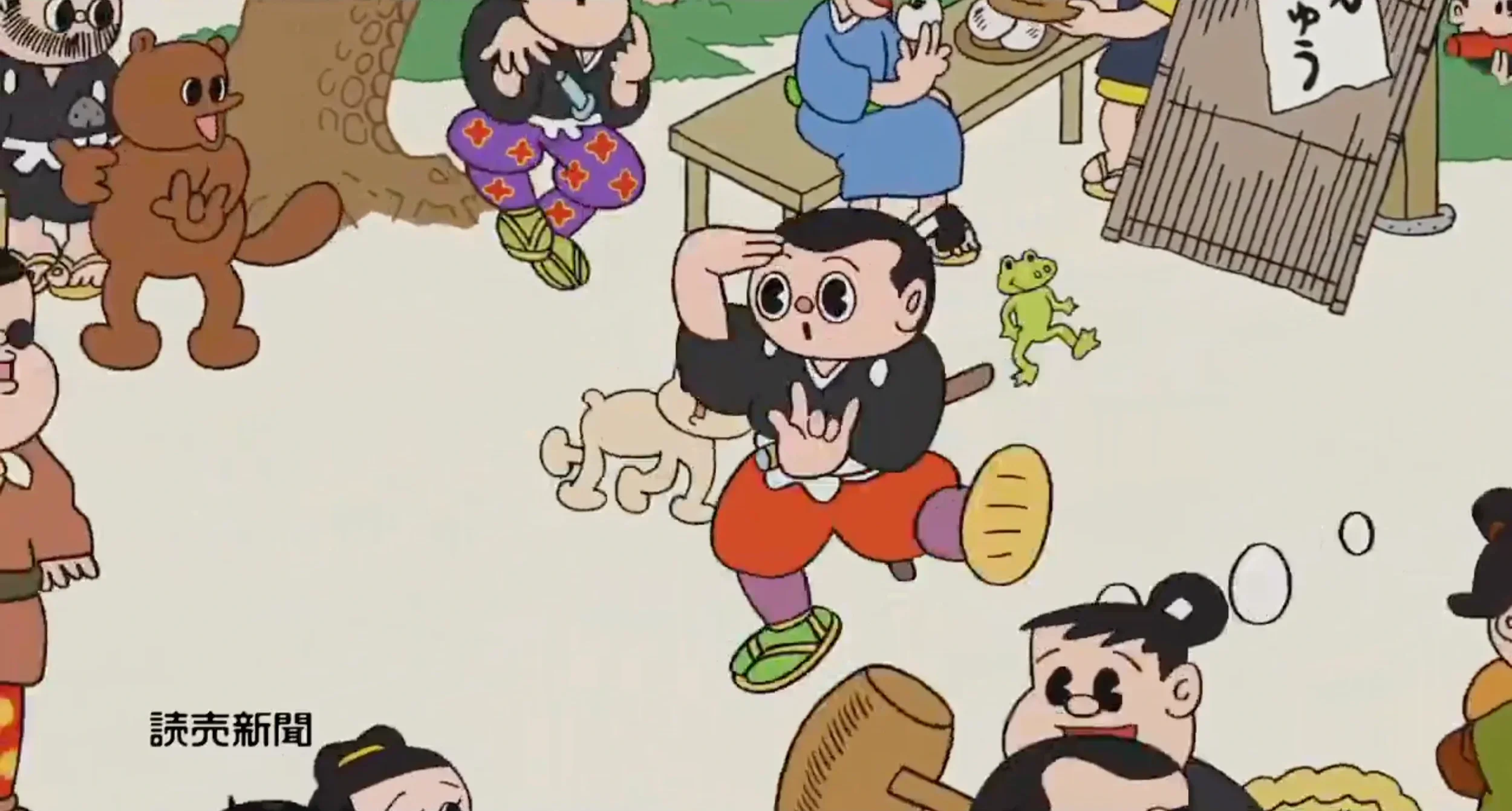

His influence radiated outward across disciplines. Gag manga pioneer Fujio Akatsuka drew inspiration from his comic anarchy, novelist Yasutaka Tsutsui and musician Haruomi Hosono counted themselves among his admirers, Isao Takahata borrowed his tanuki spirit for Pom Poko (1994) and Hayao Miyazaki even paid homage through an animated commercial. Produced by Studio Ghibli in 2009 for the Yomiuri Shimbun, the 15-second spot reimagined characters from Sugiura’s classics, Sarutobi Sasuke, Taikōki, and Happyakutanu, infusing them with fresh life. Notably, the project marked the first collaboration between Hayao Miyazaki and his son, Gorou Miyazaki, who directed the piece. The absence of any overt corporate message underlined the aim, to celebrate Sugiura’s whimsical universe and invite viewers to rediscover it on their own terms.

Studio Ghibli Commercial (2009)

Today, Sugiura’s legacy lies in the fertile space between mass entertainment and artistic experiment. His manga anticipated postmodern collage aesthetics while remaining rooted in the playful pleasures of popular culture. In this sense, he occupies a singular place in the history of manga, as a cultural bridge whose delirious imagination continues to ripple through Japanese art, literature, and animation.

How the Bokka of Oze keep the porter tradition alive.