The Japanese Magazines That Defined 90s Streetwear Culture

FRUiTS 1998│via Tokyofruits.com│© Shoichi Aoki

In the 1990s, the backstreets of Harajuku, or Ura-Harajuku, became a crucible of creativity and self-expression. Unlike the polished main avenues of Ginza where luxury boutiques catered to Japan’s growing appetite for high fashion, Ura-Harajuku thrived on improvisation. It was a space where youth remixed thrifted finds and emerging streetwear brands into wholly original styles.

The momentum behind this subversive culture grew from a mix of economic shifts, Western cultural imports, and Japan’s own rich tradition of craftsmanship. But perhaps its most important catalyst was the printed page. For many young people, fashion magazines were sacred guides.

Magazines like FRUiTS, Boon, and Kera served as windows into the streets of Harajuku and Shibuya, capturing the spirit of Ura-Harajuku in detail. Defining them as mere glossies would dishonour the work of their creators; these magazines were cultural archives and incubators. They quite literally taught their readers how to be cool and how to carve out their own identities in an increasingly globalized world.

In an era before Instagram or TikTok, these magazines were the only way to experience the pulse of Tokyo’s underground. Through curated spreads and columns, candid street photography, and detailed features on emerging brands and designers, they gave a voice to the eclectic individuals that were shaping the Harajuku we know today.

The 10 magazines featured in this article chronicled the explosion of Japanese streetwear in the 90s.

STREET Magazine

A Global Stage for Tokyo’s Streets

When Shoichi Aoki launched STREET in 1985, he likely had no idea he was laying the groundwork for one of the most influential fashion archives in the world. At its core, STREET was a photographic journey through urban fashion, spotlighting not just Tokyo but also New York, London, and Paris. Its pages juxtaposed Tokyo’s chaotic and inventive street style with the polished edges of Western urban fashion.

The magazine’s raw aesthetic was its defining feature. Each spread was a filled with candid shots, capturing real people in real environments. STREET was a grassroots celebration of individuality. The melting pot of global influences gave STREET a cosmopolitan feel, but it was always clear that Tokyo’s streets were the beating heart of its narrative.

By the 1990s, as Harajuku began to blossom into a global style mecca, STREET became essential reading for anyone wanting to understand the zeitgeist.

Street Magazine 1995│© Shoichi Aoki

FRUiTS Magazine

The Visual Diary of Harajuku

If STREET captured Tokyo’s streets, FRUiTS honed in on the chaotic, electrifying energy of Harajuku. Launched by, yes you guessed it, Shoichi Aoki in 1997, FRUiTS did more than document Harajuku’s street style. Aoki’s work amplified the voice of Harajuku, turning it into a cultural phenomenon.

What set FRUiTS apart was its celebration of the eclectic and the experimental. Each page was a riot of colors meeting patterns, and most importantly, personality. Harajuku’s youth was creating wearable art. Aoki’s photographs highlighted the endless layering, unexpected combinations, and fearless attitude of his subjects.

FRUiTS also added a very personal touch to its pages. Alongside each photo, readers found handwritten captions explaining the wearer’s inspirations, favorite brands, and thoughts on fashion.

FRUiTS’ legacy can still be felt today, as Harajuku remains a symbol of boundless creativity and self-expression.

FRUiTS 1998│via FRUiTS Magazine Archive│© Shoichi Aoki

TUNE Magazine

Streetwear’s Sophistication

Not a 90s publication, but an unmissable entry when diving into Shoichi Aoki’s magazine lineup. TUNE, launched in 2004, was Aoki’s quieter follow-up to STREET and FRUiTS. While its predecessors were raw, TUNE offered a more polished take on streetwear, reflecting the evolution of the culture into something more refined.

TUNE focused on how Japanese streetwear had begun to merge with luxury fashion. Tokyo’s youth, once reliant on thrift stores and DIY, were now incorporating high-end brands like Louis Vuitton and Gucci into their wardrobes. The magazine didn’t treat this as a loss of authenticity but saw it as a natural progression, a sign that street fashion was no longer confined to the fringes but had become a dominant force in global fashion.

Through its sleek layouts and focus on high-quality photography, TUNE captured this new era of confidence. TUNE moved beyond documenting streetwear, celebrating its newfound place at the forefront of the fashion world.

TUNE 2004│© Shoichi Aoki

Hotdog Press Magazine

The Everyman’s Guide

While many magazines zeroed in on niche subcultures, Hotdog Press had a broader appeal. Launched in the 1980s, it was initially a men’s lifestyle magazine, covering everything from dating advice to gadgets. But by the 1990s, it had evolved into a key player in Japan’s streetwear scene, serving as a guide for young men navigating this new world.

Unlike magazines that focused on high fashion or avant-garde styles, Hotdog championed trends that felt attainable. Sneakers, denim, and graphic tees were the building blocks of a wardrobe that young men could realistically aspire to. The magazine also leaned heavily on Western influences, introducing Japanese readers to brands like Levi’s, Converse, and Timberland.

It helped a generation of young men define what it meant to be cool, offering them a roadmap to navigate the intersection of style and masculinity.

Hotdog Press 1997│via 90s Yamada Koji│© Hotdog Press

CUTiE Magazine

Empowering a New Generation

When CUTiE debuted in 1989, it was an immediate hit among teenage girls. The magazine was a breath of fresh air, offering an alternative to the polished, unattainable glamour of mainstream women’s magazines. Instead, CUTiE celebrated individuality, creativity, and the DIY ethos.

The magazine doubled down on affordability and accessibility. It showcased thrifted looks, handmade accessories, and quirky combinations that felt both stylish and achievable. You were encouraged to experiment, to mix and match, and to embrace your imperfections.

CUTiE was also instrumental in popularizing trends that defined the 90s. Oversized sweaters, platform sneakers, and playful accessories became staples of the era, thanks in large part to its influence. For many young women, CUTiE was as much a community, as it was source of inspiration and a rallying cry for self-expression.

CUTiE 1993│via Ko Archives│© CUTiE

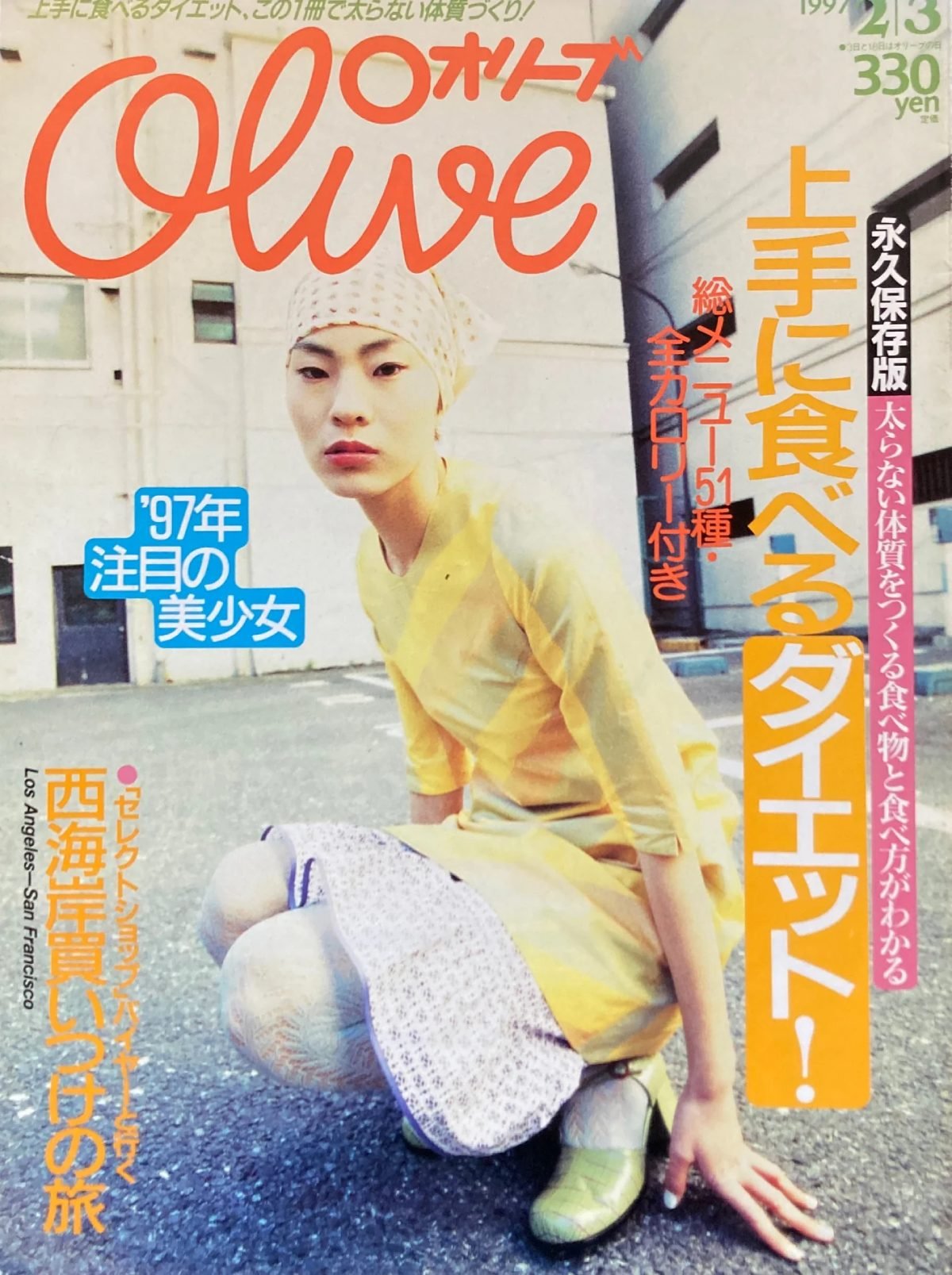

Olive Magazine

The Romantic Rebel

Where CUTiE was bold and playful, Olive was soft and introspective. Launched in 1982, Olive found its stride in the 1990s by promoting a style that could only be described as dreamy. Its pages were filled with ethereal imagery that celebrated otome (maiden) fashion, a delicate, romantic aesthetic marked by lace-trimmed dresses, ribboned hair, and vintage-inspired accessories.

Thanks to its emphasis on lifestyle, you were transported to a Parisian café or a cozy countryside tea party through the magazine’s poetic articles and evocative photography. Olive painted a picture of a simpler, slower life, one where every detail, from handwritten letters to freshly baked bread, was imbued with beauty.

For readers overwhelmed by Tokyo’s fast-paced energy, Olive was a haven. It moved beyond the realm of fashion magazines as it became a philosophy, encouraging its audience to find grace the small moments.

Olive 1997│via Smokebooks│© Olive

Boon Magazine

The Underground Innovator

If Popeye magazine, aka the famous magazine for city boys, catered to the mainstream, Boon was for the insiders. Focused on Ura-Harajuku, the backstreets of Harajuku where the most innovative fashion was brewing, Boon was the ultimate guide to underground streetwear culture.

The magazine was instrumental in championing brands that would later achieve global fame, such as A Bathing Ape (BAPE), Undercover, and Neighborhood. But Boon wasn’t stopping there, it dug deep into the stories behind these brands. Through interviews with designers and profiles of hidden boutiques, it gave readers a glimpse into the creative process that defined Ura-Harajuku’s mystique.

Boon 2005│via Ebay│© Boon

Egg Magazine

A Gyaru Manifesto

At the height of the 90s, Egg became the definitive voice of the gyaru (gal) subculture, a movement that rejected traditional beauty standards in favor of bleached hair, dark tans, and audacious outfits.

Egg was all about attitude. Its pages were filled with unapologetic confidence, showcasing young women who wore their individuality as if it were armor. From platform boots to leopard-print mini skirts, Egg’s aesthetic was proud and impossible to ignore.

The magazine gave a voice to a generation of women who felt overlooked by mainstream culture, celebrating their defiance and encouraging them to take up space.

Egg 1995│via Gyaru Fandom│© Egg

Kera Magazine

Fashion for the Outcasts

For those who didn’t fit into the mold of mainstream fashion, there was Kera. Known for its focus on alternative styles like Gothic Lolita, punk, and visual kei, Kera provided a platform for the misfits and the rebels.

What made Kera special was its inclusivity. It embraced a wide spectrum of subcultures, from the dark elegance of Gothic Lolitas to the chaos of cyberpunk. Each issue carried the mission of showing you that there was no wrong way to express yourself.

Kera created a sense of belonging for readers who often felt like outsiders. Through its pages, they found a community of like-minded individuals who shared their passion for self-expression.

Kera 2002│via Internet Archive│© Kera

Asayan Magazine

A Mosaic of Culture

Finally, there was Asayan, a magazine that defied categorization. Covering fashion, music, and youth culture, it was a snapshot of the eclectic, ever-changing world of 90s Japan.

Asayan stood out in its ability to capture the big picture, documenting trends, and exploring the cultural forces driving them. From interviews with musicians to features on underground fashion scenes, Asayan provided readers with a holistic view of the world they were living in.

Asayan 1997│via Damp Magazines│© Asayan

The 1990s were a cultural awakening in Japanese fashion, a moment when the streets of Ura-Harajuku became a canvas for self-expression. A new generation redefined what it meant to dress how you feel, not as a reflection of society. At the heart of this revolution were the magazines that gave their movement a voice.

Decades later, the influence of these fashion publications continues to ripple through contemporary fashion. The DIY ethos of Ura-Harajuku, the coverage of upcoming legendary designers, and the celebration of subcultures are now staples of global streetwear. The magazines that chronicled these moments remain timeless, their pages forever a testament to the power of youth culture.

How Ura-Harajuku planted the seeds for global streetwear culture.