Leaving Digital Traces

A chat with Kyoto-based artist nouseskou

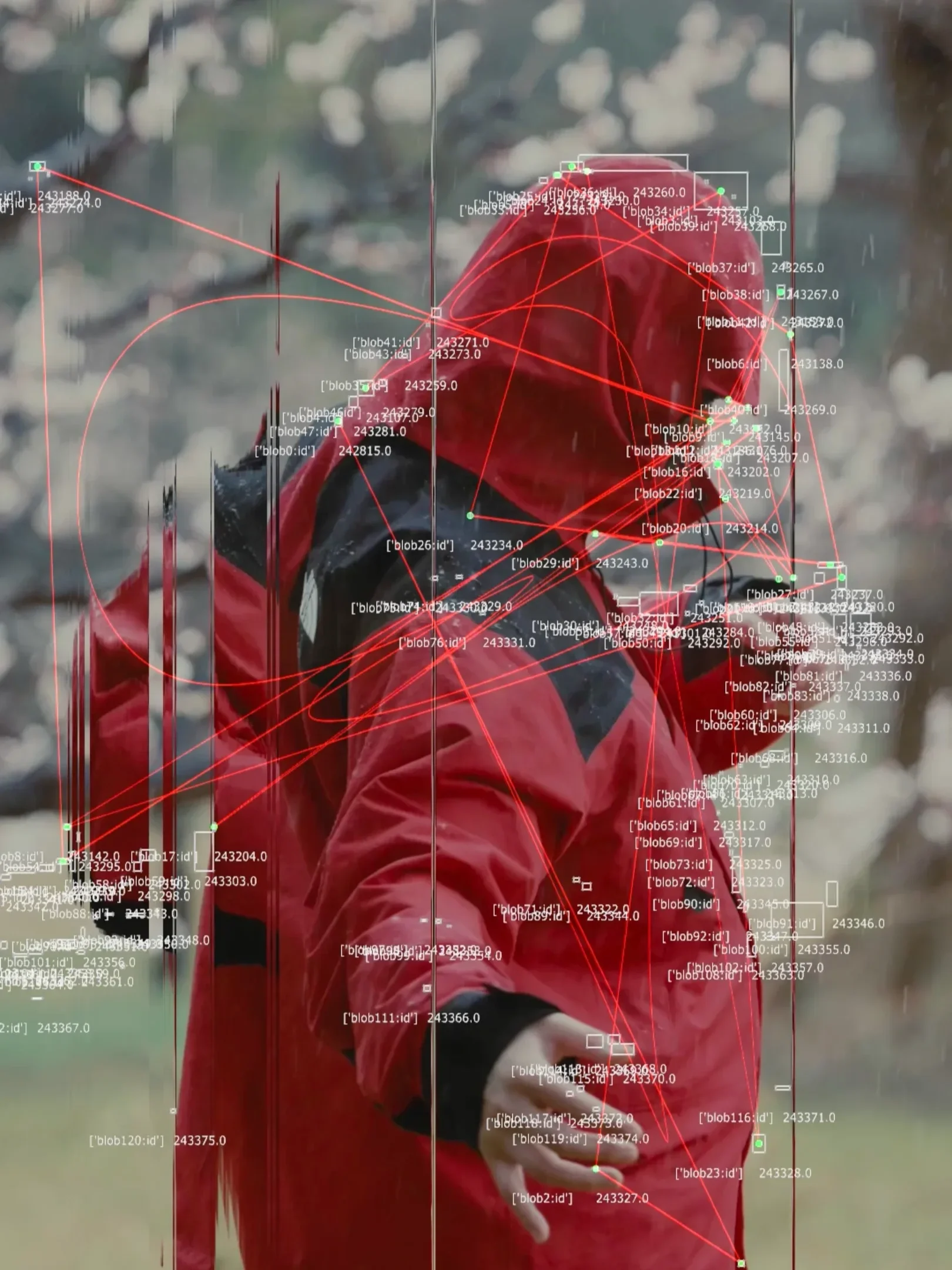

© nouseskou

Dotted patterns and warped lines trace distorted interactions with nature, bodies, and shifting atmospheres. This is the visual language created by nouseskou (Kou Yamamoto), a Kyoto-based digital artist whose work merges real-world imagery with computational overlays. In a trace that remains deeply tied to his roots, the name nouseskou combines his dance crew nouses with his own name, linking his artistic identity to Japan’s underground dance culture. Raised and still based in Kyoto, his surroundings: the forests, shrines, rivers, and the slow weight of time in the city, remain central to his perspective.

The digital interventions created by Kou are not following any fixed rules, but responding to mood, environment, and sound instead. The outcome is an evolving conversation between the organic and the technological, one that remains firmly rooted in his lived experience.

We sat down with nouseskou to discuss the mindset and vision behind these visuals.

When and how did the concept for your work first take shape?

I’m not sure when it really “began.” But maybe it started in those early moments, reaching out my hand to touch the world, and realize whether that world was this earth or something much wider, like the universe itself, just wanting to feel.

I remember shaping things in the sand as a child, chasing things without thinking, playing with no goal. That kind of sensing didn’t disappear. I think it simply continued only the tools have changed.

I started dancing in school and entered the world of street dance. Through movement, I could begin to understand who I was. Then I began to sense who the other person was. Then, the world around us. And beyond that, there are quiet moments when I begin to feel not what I must do, but how I might be able to relate to this world.

That’s not a clear answer, just something that quietly rises up from somewhere deep inside the body.

Later, I started exploring more contemporary movement and compositional ideas. Eventually, I was drawn to tools like code, video, and AI. Between the wordless sensitivity of the body, and the logical, inorganic language of technology, a silent conversation begins. And that, I feel, is what shaped the way I create now.

How do you feel your work has evolved since you started?

Rather than a clear shift, it feels more like something that was always there has gradually taken on new forms. What is visible now might just be one way something long-hidden has chosen to appear. With that in mind, I keep letting the work evolve.

What’s the influence of your environment in Kyoto?

I believe Kyoto influences my work, though not through landmarks or scenery, but through things less visible: the weight of the air, the quiet, the way time seems to drift differently here.

Kyoto is a place where layers of culture have slowly accumulated over centuries. That quiet memory feels suspended in the atmosphere, and I often sense my own perception quietly overlapping with what remains. Perhaps some part of that stillness finds its way into the work.

How do you decide which elements the digital components will interact with?

Most of the time, there are no fixed rules. It’s often guided by the feeling of the body, the density of the air, or the relationship with sound, things that aren’t visible, but deeply present. Rather than choosing digital elements, it feels more like listening to what starts to appear.

The appearance of these digital elements often change. What factors influence how you portray the visual elements in your work?

It often comes from how I’m feeling that day, an unexpected accident, a passing encounter, or something that feels like the universe gently intervening. I treat these moments playfully, in real time, improvising with whatever arises, trying to arrive at something I’ve never seen, yet somehow always wanted to see.

There’s awareness, but also a kind of drifting just beyond it, as if I’m playing in the space between consciousness and something else. Each work begins to take shape from that atmosphere, that tension, that particular moment.

Different comments claim that your work represents “overstimulation while in public”. Is this something you resonate with?

I can’t see all the comments, so this is the first time I’ve heard that interpretation. If someone felt that way, then honestly I’d like to say thank you, and I’m sorry.

I’m grateful that my work left something behind in someone’s senses, whatever that may have been. But I think I'm just playing. Noise, light, complexity, they’re all part of this world, just like quiet or breath. It’s not meant to symbolize anything in particular, it’s just there as it is. And I respond to them, moment by moment, simply playing.

Let’s focus on sound design. What elements are important to you when deciding what types of sounds to work with?

I also create sound elements on their own, but whether alone or with visuals, I’m always drawn to moments where a world I’ve never seen before feels strangely familiar.

Sometimes a sound and an image meet, and the landscape shifts, as if seen from another axis of awareness. That moment often feels like a quiet signal telling me it’s time to give the work a shape in the real world.

The sounds I choose depend on how I feel at the moment. Some days certain sounds feel distant. Others, I want to stay with them. I simply try to listen closely to whatever is present right now.

How do you decide how the sound will interact with the imagery?

It often feels like something has already been decided before I begin. Not so much a matter of choosing, but of quietly listening to what’s already there.

The relationship between sound and image doesn’t come from control, but from noticing how they meet in a moment, how they lean toward or away from each other.

What I want, or what feels right, seems to exist somewhere deep already, and the work is simply to stay close to it. That’s why explaining it too directly can sometimes make the silence drift away. I think I’m just staying beside the feeling, not shaping it.

Some people may say they can’t hear their own voice, and I understand that. Maybe it’s something that fades gradually, as we learn to adjust to the systems around us. I don’t think we need to search for it forcefully. But maybe slowly, by noticing your breath, by taking time to listen to sounds you love, by turning gently inward for a moment, that voice begins to return.

And just as importantly, allowing time to be alone can help. Not always filling the day with meetings and noise, but making space, without pressure, to simply be by yourself. That, too, might be a quiet doorway through which your voice can return.

On various occasions, you work together with your brother. What is his role, and how’s the synergy between the two of you?

My brother is a member of our dance team, nouses, and both in daily life and in creative moments, he’s someone who is naturally nearby.

In a practical sense, he often appears in my videos as another body, a presence that moves alongside mine. He’s a wonderful dancer: sensitive, intuitive, and deeply aware. There are times in a project when I feel the need for something that can’t exist alone like a relationship, a tension, or a gesture that only makes sense when shared. In those moments, I invite him into the work.

It’s never about assigning him a role or defining a task. His presence brings a kind of unspoken space into the piece, something I could never create on my own. It expands the work like a distance that invites breath.

What is next for Kou Yamamoto?

I don’t have a fixed plan for what comes next. But I feel a deep sense of gratitude for simply being able to face this moment, to do what I can today, and to be present with the expressions within my reach.

Listening to the voice within often feels like becoming part of a larger rhythm, a voice that belongs to the movement of the universe itself. And perhaps beyond that there’s a small possibility of a world that moves toward harmony. If that way of seeing can be shared with others, that alone would mean a great deal to me.

Follow the progress of nouseskou on

The cover photo of this article was taken from a work titled ‘Mountain Jack'

Year: 2025

Art Direction: Hyo Kim

Director: Marcus Gustafsson

Video: Jason Paul

While f5ve draws in the world, Crystalline Structures creates their universe.