The Dawn of Modern Japanese Prints

Onchi Kōshirō and the Sōsaku Hanga Movement

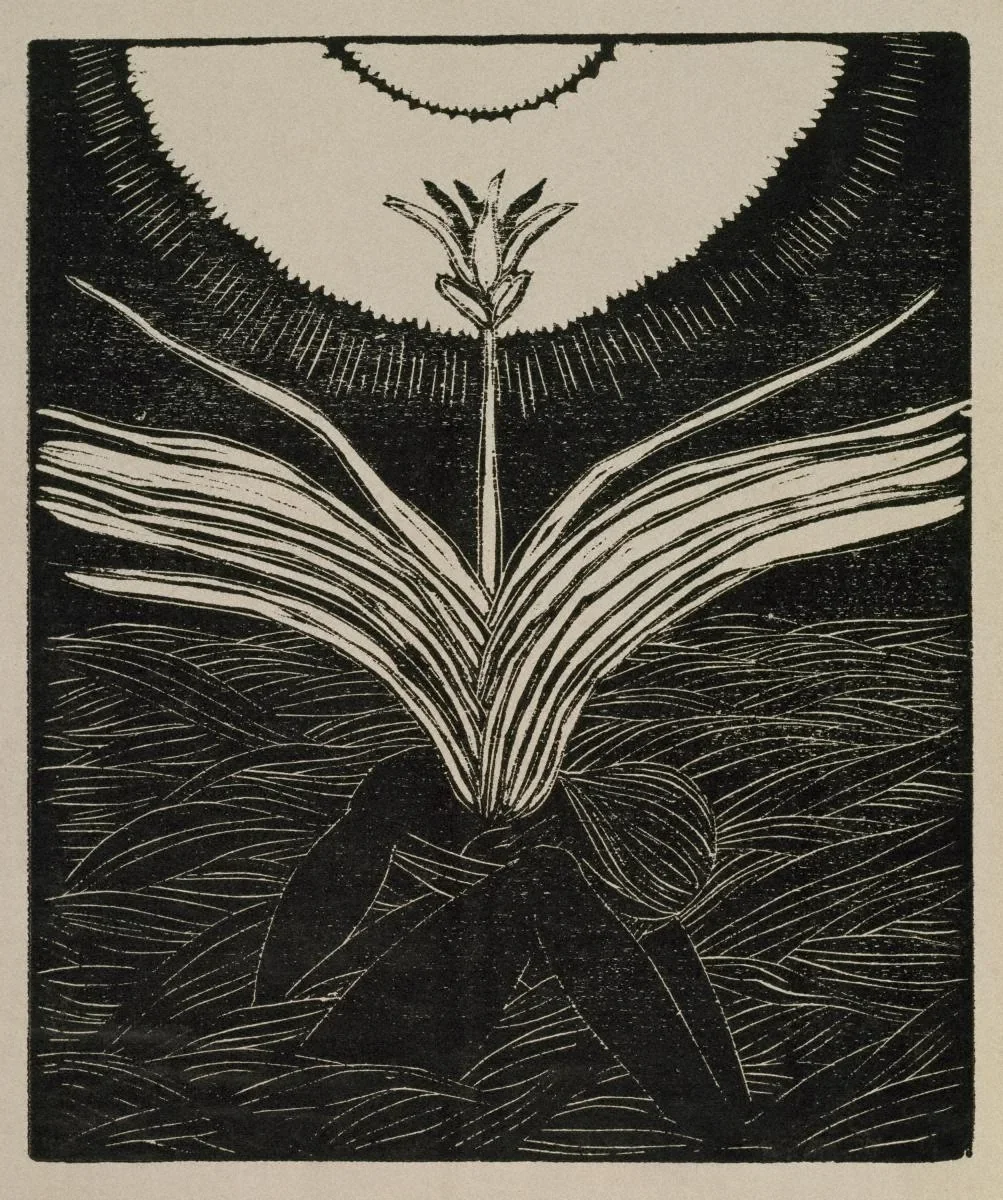

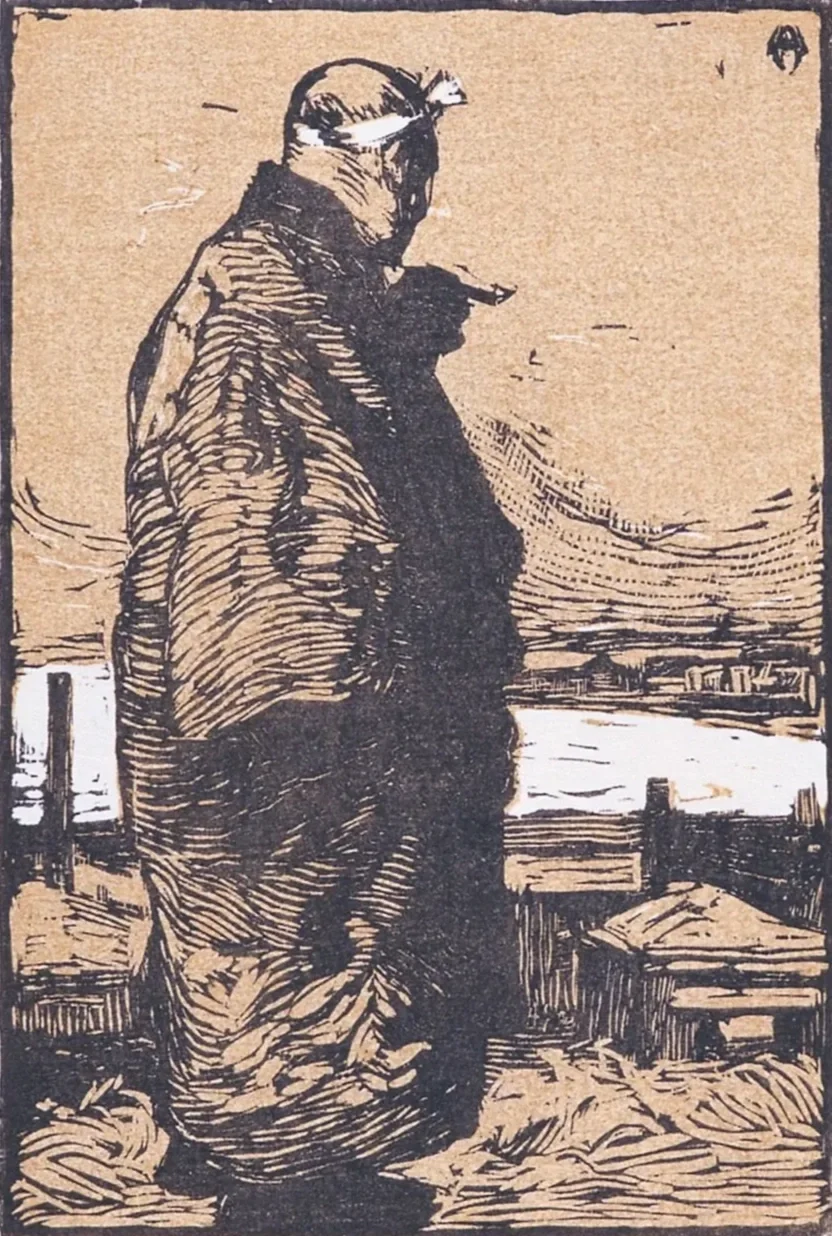

Woodcut - 1914│via Wikimedia Commons│Onchi Koshiro

When people think of Japanese art, woodblock prints are often the first image that comes to mind. And within woodblock printing, the ukiyo-e masterpieces of the Edo period, by artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige, are instantly recognizable. Yet a lesser-known chapter in the story of Japanese prints lies in the modern period that followed.

Today, Japanese printmaking is still very much alive, practiced by many contemporary artists. But the landscape and genre scenes of ukiyo-e are long gone, giving way to a wide spectrum of bold expressions and creative exploration. This shift owes much to one particular movement that emerged at the dawn of the 20th century. A movement that not only paved the way for new forms of expression, but also helped cement printmaking’s place in the art world. The movement was called sosaku hanga, and its most central figure was an artist named Onchi Koshiro.

The State of Printmaking After Edo

During the Meiji period (1868-1912), Japanese woodblock print seemed to have met its demise. Following the end of the Tokugawa shogunate’s isolationist policy, under which Japan’s foreign trade had been strictly limited for over two hundred years, things from overseas started flooding into the country. Among these were print media such as lithography, copperplate and photogravure, which quickly became competitors to the woodblock print. Not long after during the Meiji government’s elaborate modernization project, rapid industrial developments together with the introduction of mass communication led to the adoption of mechanical print technologies.

What had once been Japan’s main means of producing everything from book illustrations to printed text, was now fading away with the advent of modernization. In the age of mechanical printmaking, there was simply no need for the handcraft-based woodblock print anymore. Inevitably this also led to the decline of ukiyo-e, the production of which had been firmly rooted in the woodblock print. As the artisans of the old printmaking technique one by one went out of business, the once so popular ukiyo-e genre came to an end.

The Dawn of a New Era

It didn’t take long, however, for the woodblock print to be revived. Out of the decline of ukiyo-e, two parallel movements emerged. On one hand, there was shin hanga (”new prints”), which revitalized the ukiyo-e tradition in both imagery and production method. Mainly spearheaded by publisher Shozaburo Watanabe, this movement produced images of an idyllic Japan that echoed the ”pictures of the floating world,” at a time when the European craze for such pictures was well known domestically.

As such, these images took on a consciously exotic undertone with the aim of appealing to a foreign market. The movement moreover adopted the collective production process for printmaking that had been standard during the Edo period: first, a designer (or ”artist”) made a base sketch of the picture, which was then carved onto a woodblock by a carver, and then finally printed on washi paper by a printer - all while a publisher oversaw the entire process. Shin hanga, just like ukiyo-e, were commercial productions first and foremost, commissioned by a publisher based on customer demands.

Around the same time, another movement emerged that took printmaking in an entirely different direction, called sosaku hanga (”creative prints"). Unlike shin hanga, sosaku hanga did away with the old production system of ukiyo-e, embracing individual creation instead. With ”self-designed, self-carved, self-printed” as its core principle, the movement based itself on the idea that every step in the making of the print should be carried out by one artist.

This was groundbreaking. Not only did it free the artist from the demands and directions of a publisher, it also gave them complete creative control over every element in the printmaking process. That being said, sosaku hanga introduced a radically new way of thinking about prints as such. In the past, printmaking had been used as a mere means of reproduction. Now for the first time, the print medium itself began to be explored creatively - in other words, treated not as a reproduction technology, but as an art form.

The moment widely regarded as the birth of sōsaku hanga came in 1904 with Yamamoto Kanae’s creation of Fisherman. As the story goes, during a trip to Chiba prefecture, the artist sketched a fisherman rejoicing over a big catch, and upon returning home carved the sketch onto a woodblock and then printed it all by himself, thus creating the very first ”creative print.” Through his acquaintance with Ishii Hakutei, whose family he sojourned with at the time, Fisherman was published in that year’s July issue of the magazine Heitan.

Fisherman│via Wikimedia Commons│© Yamamoto Kanae

With a shared interest in the art of printmaking, Yamamoto and Ishii banded together with artist Morita Tsunetomo to form the magazine Hosun in 1907, in which they published artworks in various print media together with poetry, essays and reviews. In one of the magazine’s first issues, they declared that “right now the creative prints in Japan can only be seen in our magazine.” However, their use of the term ”creative prints” was quite loose, as the magazine included plenty of works carved and printed by external artisans. To them, creative printmaking was not defined by individual creation, but was rather a general description for prints with a “creative” or artistic quality. So while Yamamoto Kanae and his colleagues were responsible for the birth and adolescence of sosaku hanga, it had yet to fully mature into a defined movement. This maturity came with the next generation of artists, and among them the endeavors of one artist in particular.

Onchi Kōshirō - Champion of the Creative Print

Onchi Koshiro was born in 1891 in Tokyo to an aristocratic family. Through his father Onchi Tetsuo, who worked as a secretary for the imperial family, he received education in Japanese history and literature as well as calligraphy at a young age. His father intended for him to become a physician, and enrolled him in a middle school with a medicine-focused education. But Onchi himself was not very enthusiastic about his father’s plans for him, and eventually failed the entrance examination for the prestigious high school that he was expected to attend. With an interest leaning more toward the arts, in 1909 at the age of eighteen he entered the art institute Hakubakai to study oil painting.

While there, he came across the first published art book by Takehisa Yumeji. The young Onchi was entranced, and wrote a fan letter to the artist expressing his admiration. Yumeji responded with a suggestion that the two should meet, which became the start of a several year long mentor-student relationship, with Onchi receiving personal training and advice from the senior artist. Even though Onchi already had a strong artistic interest, his acquaintance with Yumeji was the impetus that led him to seriously pursue the career of an artist.

Around this time, it was the norm that such a career path should start with a formal education at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, and so in 1910, Onchi enrolled in the university’s oil painting curriculum at the encouragement of Yumeji. However, dissatisfied with his education, he quickly switched to the sculpture department, then back again to oil painting, until finally dropping out. It was clear that his creative interests lay elsewhere, outside of the academic education system and its ”traditional” art forms. He found his calling in printmaking.

At the Hakubakai institute, Onchi became close friends with classmates Tanaka Kyokichi and Fujimori Shizuo. As all three then proceeded to the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, they began making woodblock prints together outside of their designated curriculums. They decided to form a magazine to display their art in, and so in April 1914 the first issue of Tsukuhae was published. Up until its final issue in November 1915, Tsukuhae acted as the hub for their printmaking activities, with each artist’s equally idiosyncratic expressions filling up its pages.

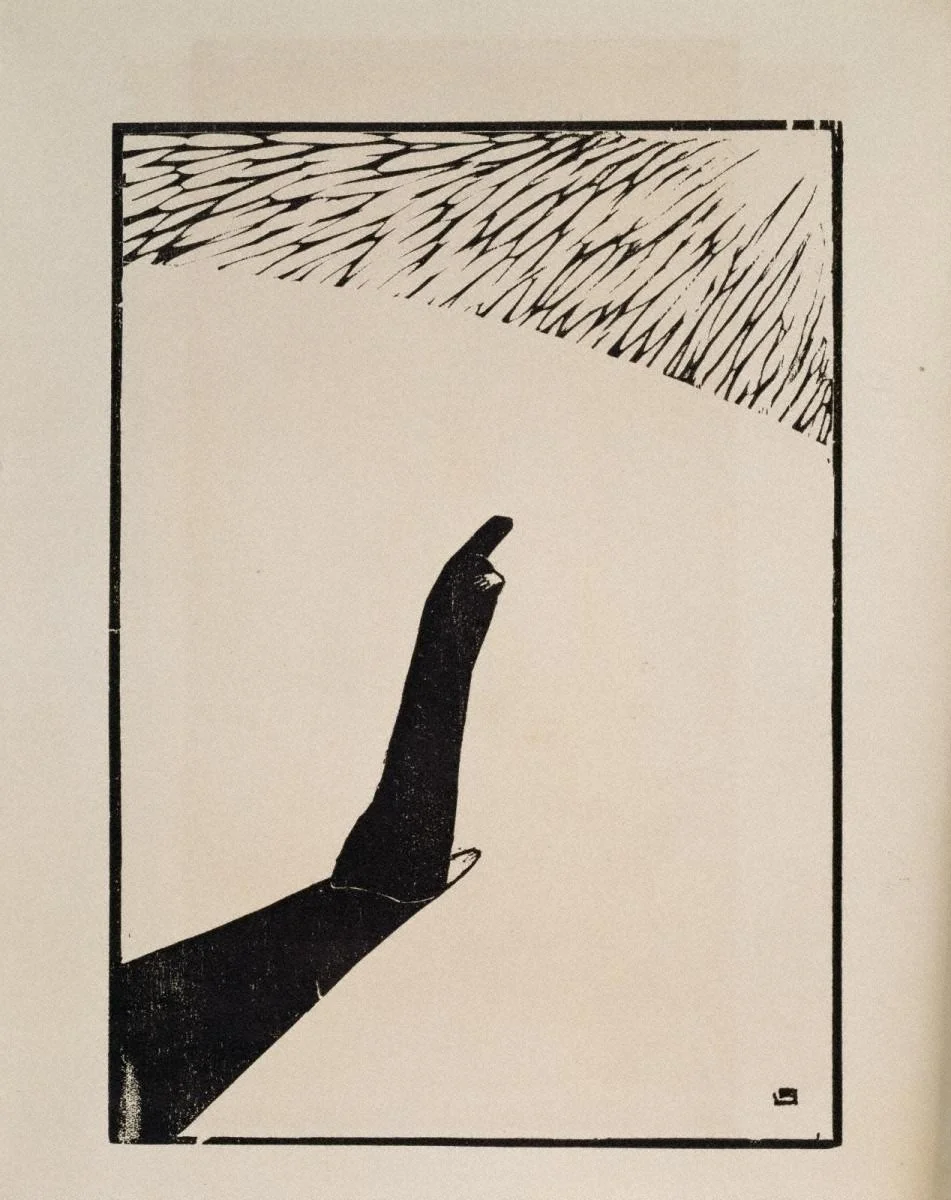

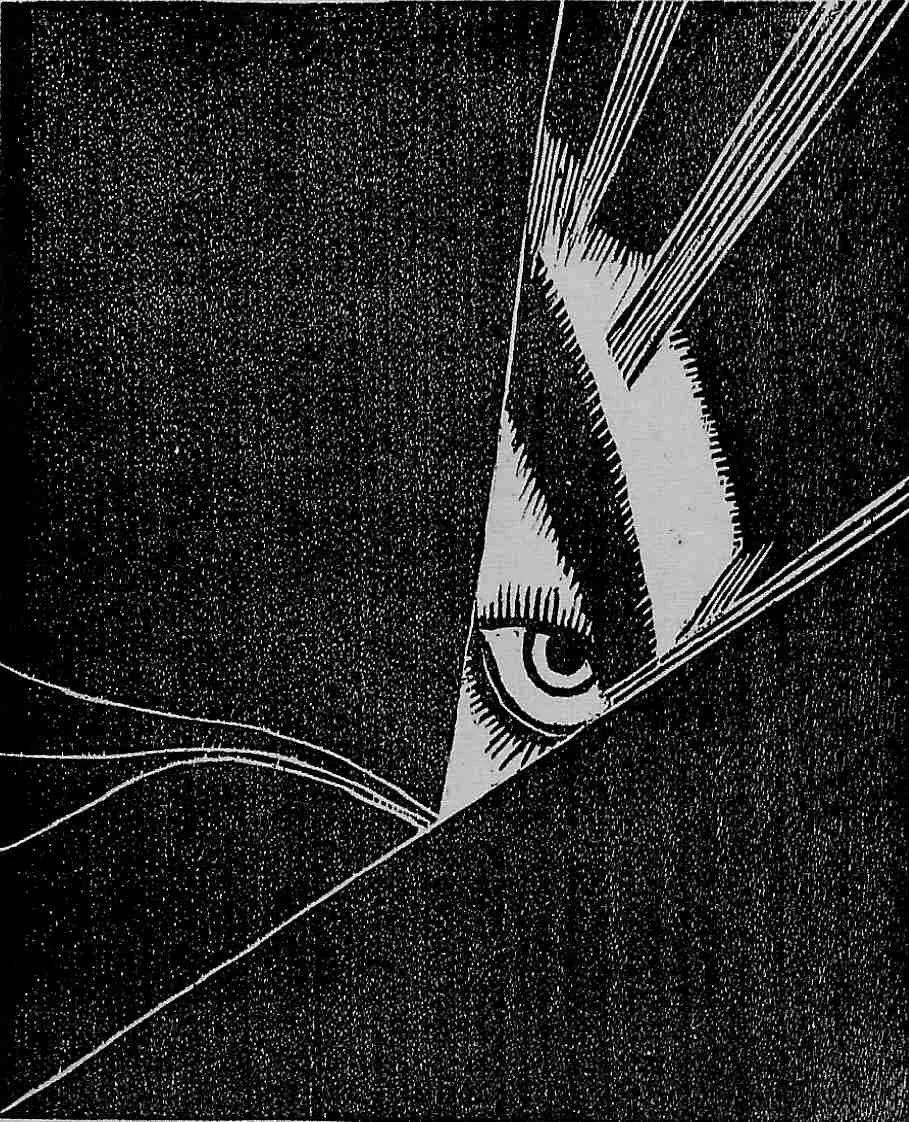

There was Tanaka Kyokichi’s fragile yet haunting depictions of human bodies juxtaposed with nature; melancholic introspections on death and mortality that reflected his own tragic struggles with tuberculosis. There was Fujimori Shizuo’s ethereal uses of light and shadow along with empty space, as a way of exploring his fascinations with the soul and the cosmos. And then there was Onchi Koshiro himself, with one bold experimentation in compositions, shapes and colors after the other, as if continuously wanting to test the limits of what could be done with the medium.

If Hosun had opened the doors for ”creative prints” as an idea, then Tsukuhae energetically put it into practice. As short-lived as it was, the magazine left a pivotal mark by giving the sosaku hanga movement a clear identity, as well as setting a standard for its creative horizons.

After Tsukuhae’s discontinuation, Onchi Koshiro would spend the rest of his career fighting for the movement that he and his classmates had helped forge. In 1919, he became the leader of the Japan Creative Print Association, taking over the mantle from Yamamoto Kanae. This association, which had been formed the year prior by Yamamoto and three other artists, became the center for the sosaku hanga community.

On top of regularly arranging exhibitions where the printmakers could display their art, the association pushed for this art to be accepted by the academic establishment. At its early stages, three main goals were set up:

The publication of a book on how to make prints

The inclusion of prints at the government-sponsored Japan Fine Arts Exhibition (also known as Nitten, or Teiten at that time)

The formation of a printmaking curriculum at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts.

As leader of the association, Onchi was at the forefront of these efforts, continuously grinding the way for the movement in an environment that refused to recognize printmaking as an art form.

Throughout its years sosaku hanga remained an underdog movement, even after the association’s three goals had been accomplished. But in the early postwar years, this took a turn. It all started in 1946 when Onchi Koshiro was contacted by William A. Hartnett, a recreation director stationed in Japan during the US occupation, who suggested to arrange an exhibition for the American soldiers. The exhibition became a huge success and shortly led to several follow-ups, one of which was visited by the civilian employee Oliver Statler in the spring of 1947. Having been unimpressed by the idyllic images of ukiyo-e and shin hanga, Statler immediately fell for the much more exciting expressions of these prints. Through Hartnett, he bought several prints and eventually came into contact with Onchi himself. With the three of them sharing sentiments about the artistic richness of sosaku hanga, they started working together to promote it internationally. Statler’s seminal book Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn became the first comprehensive English-language introduction to sosaku hanga. It was published in 1956, only one year after Onchi’s passing, and was dedicated to him.

Through the collaborative efforts of Onchi, Hartnett and Statler - alongside the unexpected success of sosaku hanga artists at the 1951 São Paulo Biennial - an international market for creative prints started to emerge. This market was in need of a retailer. A young man named Yuji Abe saw the opportunity, and decided to open an art gallery that would focus on modern and contemporary print art. In 1953 the Yoseido Gallery opened its doors in Tokyo’s Ginza district. Thanks to an effective ordering system, it became the main exporter of sosaku hanga during its prolific years of international recognition in the 1950s and 60s, with customers ranging from private collectors to museums. The founding of the gallery was not just on Abe’s own initiative however, but at the recommendation of none other than Onchi Koshiro.

From his years as a young art student until the very end of his life, Onchi Koshiro continued being at the forefront of the sosaku hanga movement, tirelessly fighting for its growth and success.

© Shizuo Fujimori

Printmaking as Art

Out of all the sosaku hanga artists, Onchi was by far the most outspoken regarding the artistic value and principles of printmaking. He once expressed that ”the print is an art form that makes use of its creative process as a means of expression.” In other words, he thought that the specific creative process of printmaking allowed for unique artistic expressions that couldn’t be accomplished in any other art form. But in order for those expressions to be accomplished, the artist’s sole execution of the entire process was essential.

Even though Yamamoto Kanae’s Fisherman had been the first case when such a sole execution was put into practice, as aforementioned, the practice did not continue into the activities of Hosun, with many of its published works being carved and printed by external artisans. It wasn’t until Tsukuhae that ”self-designed, self-carved, self-printed” was formulated as a core principle for the movement and the definition of ”creative prints.” In fact, Onchi himself came to criticize the content of Hōsun, stating that ”many of its works are not creative prints.” For him, only a print created entirely by one single artist could be considered ”creative,” and, furthermore, only a creative print could be considered art. This meant that he also rejected the prints of ukiyo-e from the definition of art. Onchi Koshiro and the Tsukuhae group’s idea of art and artistry was closely tied to ideas of individualism.

These sentiments were very much a reflection of the time, shared by the broader artistic environment of the Taisho period (1912-1926). In the wake of on one hand the political currents of ”Taisho democracy,” on the other hand the influx of European modern art such as post-impressionism, expressionism and cubism, an avant-garde made its way as a reaction against the academic art system that had been established during Meiji. In opposition to the values of beauty, naturalism and Japanese tradition that were being taught at the national art schools, a new generation of artists propagated individualism and self-expression as the essence of art. The centerpiece of this avant-garde was the Shirakaba group (active from 1910 to 1923), a collective of artists and writers who published a magazine of the same name, where illustrations and printed artworks shared the pages with essays, opinion pieces, poetry and fiction. On top of that they also arranged a number of exhibitions, featuring the art from Europe that they took inspiration from.

The activities of Shirakaba made a huge impact on young artists at the time, exposing them to the bold and exciting art from overseas together with liberating ideas of artistic individuality. One of these young artists was Onchi Kōshirō, who enthusiastically both read their magazine and visited their exhibitions. Moreover, Shirakaba co-founder Mushanokoji Saneatsu, who wrote much of the magazine’s essays on individualism, was someone who Onchi looked up to as a mentor and even acquainted with in 1915. These connections most certainly influenced his own individualist views on art and printmaking, which in turn greatly shaped sosaku hanga’s identity as a movement.

A Pioneer of Abstraction

Although Onchi Koshiro explored a vast range of styles throughout his career, the undeniably most significant of these was abstraction. His interest in the abstract was rooted in an interest in self-expression. As opposed to the academic art establishment’s emphasis on faithfully depicting the surrounding world, Onchi turned inward, using his art as a means of expressing his inner self. Once again, this was very much reflective of the individualist attitudes from the Taishō avant-garde and Shirakaba in particular. At the same time, Onchi was also heavily influenced by Russian abstract painter Wassily Kandinsky, whose art he first encountered at the Der Sturm exhibition held in Tokyo in 1914, and whose spiritualist aesthetic philosophies he subsequently studied.

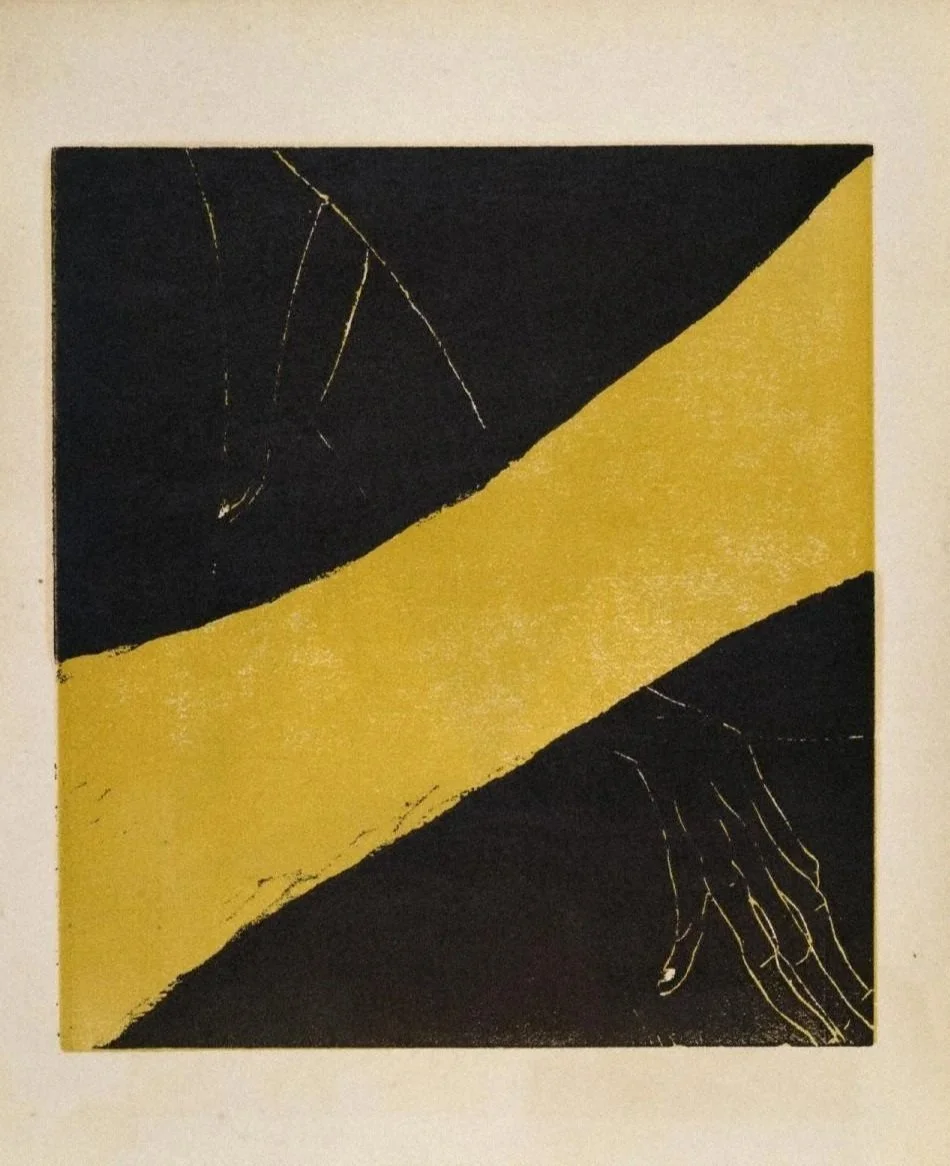

Onchi’s use of the abstract as an expression of the inner self can most strongly be seen in Lyric: a series of works that spans across the artist’s entire career. Onchi himself described the aim of these artworks as follows: ”The heart flows into the hand, and the hand rushes onto the paper. That is where my lyrical pictures come into being. […] These works arise purely from within.” Beginning in semi-figurative territory, the series quickly abandoned discernible figures altogether for a visual landscape consisting purely of shapes and colors. The first fully abstract work in the series was The Clear Hours, published in Tsukuhae in 1915. In fact, this particular print is widely considered to be the very first abstract work by a Japanese artist.

The Lyric series is in many ways representative of Onchi Koshiro’s artistry as a whole. It is a result of his different influences, but also showcases how he used those influences to create a truly unique and personal body of work. As pioneering works of abstraction, the series truly demonstrates his creative and innovative spirit, and the ways in which he pushed the envelope not just for the Japanese print but for Japanese art at large.

The Clear Hours│1915│© Onchi Koshiro

Lasting Impact

The legacy of Onchi Koshiro and the sosaku hanga movement lives on in more ways than one. In 1931, the Japan Creative Print Association merged with the Western Style Print Association to form the Japan Print Association, which to this day is active as a major community organization for Japan’s print artists, with frequently held exhibitions and hundreds of members. Yoseido Gallery is still in operation since 1953, selling and exhibiting prints by both big names from the sosaku hanga period and the many artists that have followed in their footsteps.

Furthermore, it is safe to say that Onchi Koshiro and his fellow printmakers have left a definitive mark on the Japanese art world at large. One might wonder what contemporary Japanese prints would’ve looked like without the creative printmakers’ radical artistic explorations. Or, one might ask if printmaking would even be considered ”art” in the first place, if it wasn’t for the endeavors of the sosaku hanga movement.

How the Bokka of Oze keep the porter tradition alive.