Oze’s Bokka - Inside the World of Japan’s Mountain Porters

courtesy of Hagiwara Masato

A few summers ago, on a day where the air was so thick it felt like breathing through a wet towel, I stood before the mausoleum of Tokugawa Ieyasu, ultimate victor of the Sengoku period and one of Japan’s most influential figures. I had trekked through winding, cedar-flanked paths alongside a slew of people all, no doubt, as fascinated as I was to see a tangible remnant of the man who cobbled together enough alliances by pen and sword to unify Japan and usher in a 250-year-spanning dynasty.

Ascending the steep hill alongside the persistent drone of cicadas and feet scraping dirt, old ladies zipping past me with ease as my northern European bronchioles withered in the humidity, I arrived at Toshogu, a temple complex where Ieyasu is enshrined. At its front resplendently sits the Yomeimon, an ornately decorated gate that explodes outwards with intricate carvings and geometric shapes so beautiful they almost hurt to look at. Behind it is a storehouse adorned with the Three Wise Monkeys of Toshogu imploring you to speak, hear and see no evil.

Despite being on such historically hallowed ground, surrounded by architectural wonders that I’d walked and walked for, Tokugawa Ieyasu was far from my mind, and my eyes were transfixed on something completely different: a man who looked well into his sixties in a clean white shirt and black trousers, a hand towel wrapped around his neck and a spear of boxes piercing the sky about a foot above his head. I was mesmerised. Weaving through the crowd splayed before him the way a fly moves when you try fruitlessly to swat it, he manoeuvred himself up steps and slopes without so much as a wobble of his precious cargo. Even though I know my way around a crow pose, the combination of balance and speed had me rubber-necking until he was completely out of my sight.

This was my first encounter with Japan’s bokka.

Essential Workers

As long as people have lived around mountains, there have been bokka, a type of porter associated with delivering goods to hard-to-reach places. Up until the Sengoku period (1467–1600), bokka were the primary means of getting something from one place to another, but with the wide adoption of horses over time, bokka were relegated to more uninviting terrain that, due to a lack of adequate mapping, required knowledge of the local land and weather patterns to deliver essential goods to monks in remote monasteries and operators of mountain huts. While being a bokka was a profession in itself, often their ranks were swelled by farmers wanting to make some extra money outside of harvesting season. But in any case, walking up mountains in rain and snow with around 60 kilograms strapped to their shoiko (specialised ladder-like backpacks) required considerable skill, whoever was doing the heavy lifting.

courtesy of Hagiwara Masato

The March of Modernity

With Japan’s industrialisation during the Meiji period (1868–1912), bokka found themselves in lower demand than ever before as paths were cleared for train tracks and vehicle-friendly roads. However, the spirit of these mountain porters still survived. In one truly fascinating example, bokka Omiyama Tadashi carried a huge screw-shaped toposcope weighing around 250kg to the summit of Mt Hakuba in two trips in 1941. Looking at the gigantic slab of eternal stone now, still perched exactly where Omiyama left it, is a permanent reminder of the potential power of a cosmically determined mountain porter with a package to deliver.

Interest in the bokka has also recently revived thanks to game director Kojima Hideo, and I certainly count myself among those newly intrigued by these nature-defying postmen. While I’ve always been obsessed with Metal Gear Solid, I missed the boat on Death Stranding when it first released back in 2019. But, with the recent release of Death Stranding 2 and a considerable amount of time on my hands, I blitzed through the first and just finished the second, and an embarrassing amount of hours later, I became obsessed with bokka. I loved the virtual trudge and toil of it all, and became addicted to delivering my little imaginary parcels to imaginary people. And you can even meet a guy who calls himself The Bokka, choosing the Japanese term because ‘I walk the earth on my own two feet and I carry the load on my back alone.’

The Bokka of Today

In the real world without exoskeletons, questionable physics and the ability to balance any weight on your back by holding the L2 and R2 buttons simultaneously, bokka are out there today, mesmerising tourists in Nikko and, more importantly, delivering the goods to whoever needs them. Today, bokka as a profession is best preserved in Oze National Park, which spans Gunma, Fukushima, Tochigi and Niigata. The park’s most famous area, the Ozegahara marshland, is truly breathtaking. Boardwalks sit swallowed by dense white skunk cabbage and tall grass, the ground dotted with hundreds of pools reflecting shimmering images of Shibutsusan and Hiuchigatake, two mountains in silent watch over the marshes. And if you’re lucky, you may just see a bokka or two.

Interest from the public has grown as bokka have become a rarer sight, and it’s not hard to see why. Bokka put immense thought into every part of the preparation. Their cargo, often made up of fuel, cardboard boxes filled with food and cans of beer totalling around 100kg, is arranged onto their shoiko like puzzle pieces to ensure that the centre of gravity sits slightly above their heads. When loading the pack onto their backs, they lean it delicately against a wall, ensure the parcels are packed tightly, and then squat down, standing back up with the momentum of the shoiko falling onto their backs. Their walking style, too, is indicative of this thoughtfulness. To prevent any possibility of losing balance while traversing Oze’s narrow boardwalks and steep inclines, they walk slightly hunched with their arms folded, hands wedged tightly into the gap between their thickly padded shoulder straps. Their faces are always trained on the ground directly in front of them with a gaze of complete concentration.

In 2019, a Korean documentary team released The Speed of Happiness that follows Oze bokka through their difficult and precarious routes. And while it is easy to over-philosophise, to expect that these seasonal workers providing an essential service to those in need do what they do for a higher purpose, it is hard not to be struck by their mindsets and their determination to keep walking, even when winds batter their faces and make every step a risk. ‘Although I walk the same route every day, it feels new each time I do it’, remarks a forty-nine-year-old porter to the camera as he places his feet carefully along a well-trodden, although perilously icy, path.

The bokka featured in this documentary also have their own YouTube channel, ‘Japanese Porter’, who share videos of their work to express ‘the story we carry with every step.’ Watching these videos, it becomes clear that there is a fierce comradeship among the bokka. One porter passing another taking a rest by the side of the boardwalk share remarks about the heaviness of their packs and laugh with each other. During winter, they shovel snow together, and they discuss the best ways for each to arrange their day’s cargo. Without each other, it’s clear that the burdens on their backs would fall much heavier on their shoulders.

courtesy of Hagiwara Masato

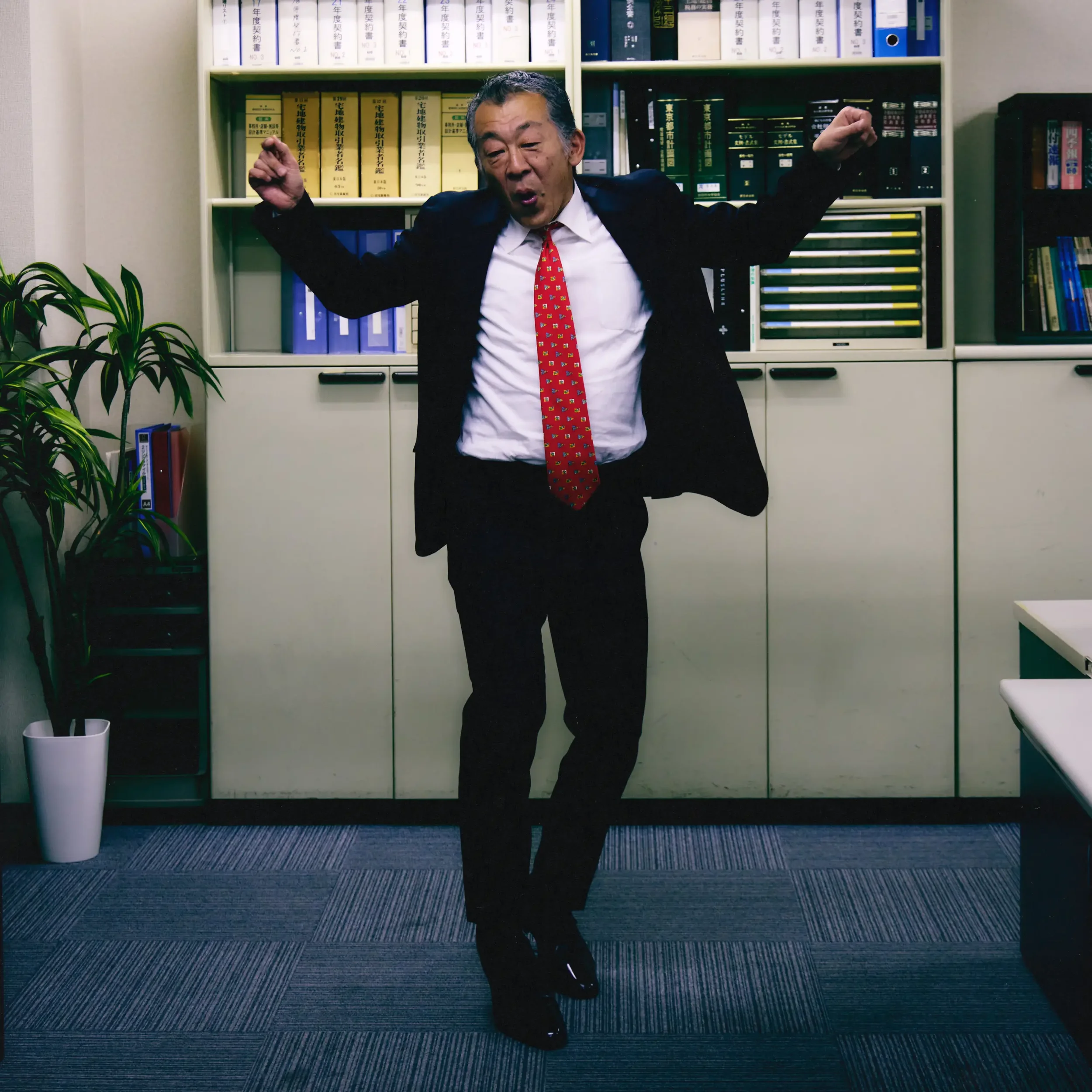

Hagiwara Masato – Oze’s Native Son

Fascinated with what it takes to become a member of such a small community, I reached out to Hagiwara Masato, one of the bokka who feature on ‘Japanese Porter’. Hailing from Katashina, a tiny village of around 4,000 within Oze National Park, Hagiwara is a slight man whose 65kg frame betrays neither the sheer volume that he can carry nor his exceptional endurance and tenacity in harsh conditions. With a boyish grin, smiling eyes and shoulder-length hair covered by a bucket hat, he cuts the figure of a modern-day adventurer decked out in AIRism and unshackled from the tedium of city life. And for Hagiwara, who grew up among the mountains he would one day traverse for a living, this couldn’t ring more true. After moving to Tokyo for school, he realised that, now in one of the most densely populated places on Earth, he missed being surrounded by nature and living in harmony with it. At age 21, he returned to Oze and began his training, working his way up from a 30kg load to regularly delivering cargo weighing 90kg. By his fourth year of working as a bokka, he could haul 120kg at a time between the mountain huts of Oze. Suddenly, talking to Hagiwara, Omiyama’s feats of old don’t seem so impossible.

Now aged 32 and eleven years into his porter career, Hagiwara still finds newness in treading the same routes that lead back to his childhood. ‘Every year, every day, I realise just how different things are,’ he said, and in Oze, the difference between days can be stark: verdant in the spring and summer, sun-dappled auburn in the autumn and almost impossibly white in the winter. Hagiwara finds that he must lean into this flux, his movements adapting to fit the conditions he finds himself in. ‘Living surrounded by nature means living each day with effort. I feel like I’m still learning to live authentically and with flexibility’, he says.

Not only does this change in seasons bring worse weather, but also a fall in demand. At around a two-hour drive from Tokyo, Oze is a perfect destination for a quick hiking getaway, but the thick sheets of snow that cover the mountains and marshlands in winter mean that the national park closes until the new season, and with it the mountain huts that bustled with visitors in the months prior. And when monthly salaries for bokka even in the high season sit at around 200,000 yen (almost £1,000), this plummets in winter. As such, porters like Hagiwara have diversified. On top of taking more deliveries for large-scale construction projects, Hagiwara is a ski instructor during the winter, and has recently begun beekeeping and selling honey.

Hagiwara chalks all of this up to the natural fluctuations of living with the fickle whims of nature, and is keen instead to focus his thoughts on gratitude. He visualises himself as a small part of a much larger chain of people that make all of his jobs possible: ‘Oze’s nature exists, people visit it, they stay in mountain huts, and they need supplies. Being a bokka is possible because of this. I’m grateful to everyone.’

courtesy of Hagiwara Masato

What Next for the Bokka?

With a profession like this, paradoxically focused on maintaining an ancient, unchanging job of moving things to and fro while also continuously adapting to an ever-changing environment, it seems natural that Hagiwara’s thoughts drift towards the concept of change. While he claimed that, ‘even after eleven years, I feel the same as always – the only thing that’s changed is that I carry more processed foods,’ he sometimes made known a looming uncertainty for the future of his profession and mountain home. ‘The area has fewer children now. The candy store is gone, and I don’t see children playing outside anymore. When I was a child, we were all always playing outside,’ he said. Perhaps fatherhood has changed his way of thinking, and now that his four-year-old daughter recently trekked 9km with him – something that he’s immensely proud of – legacy and passing the torch may be creeping into his mind.

Speaking with Hagiwara made it clear that being a bokka in today’s hyper-modern society is a choice, one that puts environmental consciousness at the heart of a lifestyle and that’s only made possible by like-minded people sharing a vision. I think back once again to The Bokka in Death Stranding 2, who tells my blood-spattered avatar of Norman Reedus that ‘You could count on bokka to make deliveries – no matter how treacherous the terrain or remote the destination. And I try to live by their example.’ Living with effort, it seems, is no light matter.

courtesy of Hagiwara Masato

Ricardo Paredes reframes anime through Renaissance and realism.