How Japan Led the Early Poly Art Style

Final Fantasy VII│© Square

When the video game industry first stepped into the world of 3D graphics, polygons were a technical limitation rather than an artistic choice. Machines could only render a handful of solid shapes at once, and every extra edge risked dropping the frame rate into unplayable territory. Yet it was in this restricted environment that the Japanese game industry managed to do something the rest of the world did not: turn low-polygon graphics into a cultural style.

While polygonal experiments appeared earlier in the US and the UK, such as Maze War in 1974, Battlezone in 1980, and the many flight simulators that pushed military and PC graphics forward, these projects focused primarily on simulation and technical demonstration. Their visuals were functional and often austere, not yet connected to character-driven entertainment.

Japan’s approach differed fundamentally because its move into 3D took place on consumer-focused game consoles and arcades, where emotional appeal mattered as much as technical progress. In the early 1990s, Japanese hardware companies began integrating polygons directly into the devices millions of players already owned or encountered in public game centers. Sega’s Model 1 arcade board brought Virtua Racing and Virtua Fighter into arcades starting in 1992 and 1993, transforming geometric figures into fully controllable fighters and drivers.

Nintendo, working alongside Argonaut Software, embedded the Super FX chip into Super Famicom cartridges, allowing Star Fox in 1993 to deliver its angular spacecraft and polygonal worlds straight to living rooms. Shortly after, the arrival of the PlayStation in 1994 and the Nintendo 64 in 1996 turned 3D from novelty into standard, establishing a global baseline for how interactive characters could look and move in polygonal form.

The change was not only technological. Japanese designers made distinctly artistic decisions that shaped how the world would interpret polygons. Rather than chasing realism, they prioritized optimization of every model for readability and personality. Characters needed recognizable silhouettes even when constructed from only a few dozen shapes, and their movement had to express who they were. The sharp limbs and big hands in Virtua Fighter, the exaggerated outlines of Mario in Super Mario 64, and the iconic proportions of Cloud Strife in Final Fantasy VII were clever solutions to strict polygon budgets that later became defining elements of early 3D aesthetics. Strong color blocking replaced detailed textures, and fluid animation delivered emotion that geometry could not yet support.

At the same time, developers in the United States and Europe were pursuing different priorities. The PC market, where Western studios operated most strongly, rewarded realism and technical fidelity. id Software’s Quake, Looking Glass’ System Shock, and other groundbreaking titles pushed graphical performance, lighting, and immersion, but their characters were often secondary to their environments or technology. Early first-person shooters placed the player behind the gun rather than presenting a memorable avatar on screen.

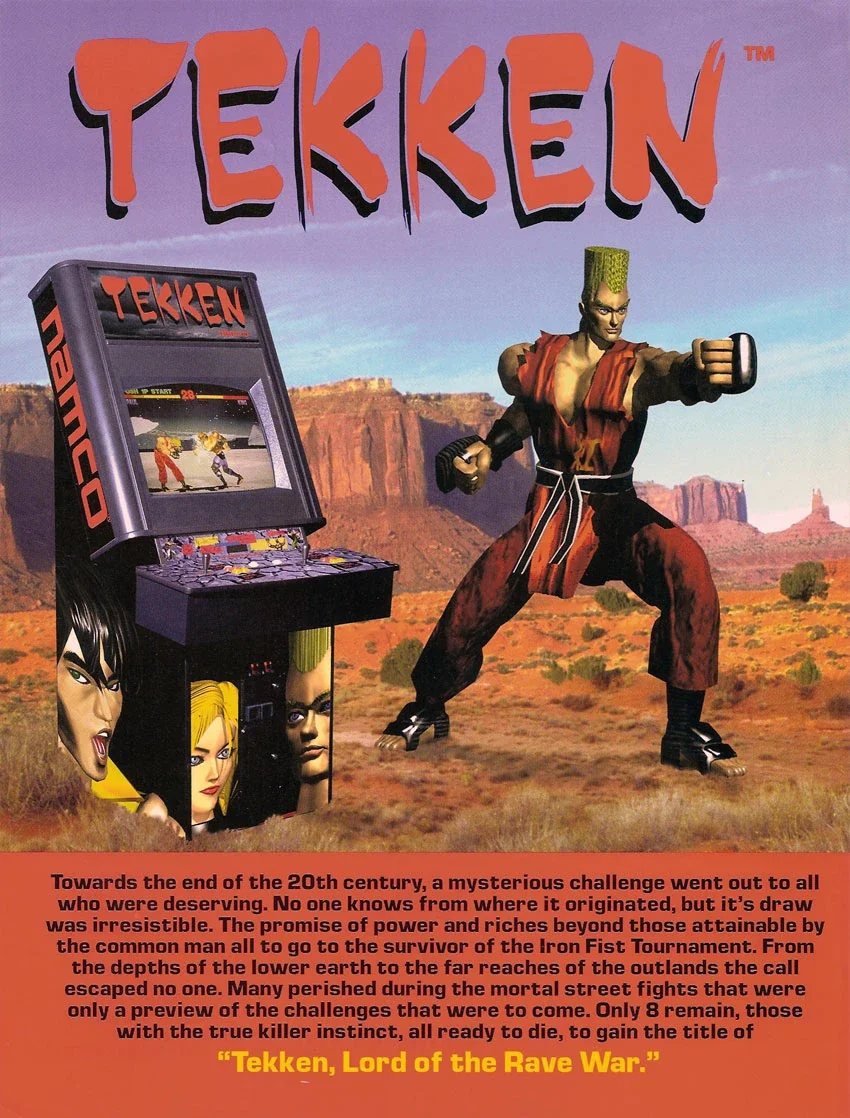

Before that Western shift toward 3D mascots, Japan had already released a significant number of polygon-based character games into the commercial mainstream. Sega introduced fully 3D fighters with Virtua Fighter in 1993 and refined them with Virtua Fighter 2 in 1994. Namco answered with Tekken in 1994, establishing its own roster of stylized polygonal personalities. Sega continued exploring stylized low-polygon character design with Panzer Dragoon in 1995, and Sony’s Jumping Flash! the same year experimented with platforming in true 3D perspective even before Mario made the leap. Battle Arena Toshinden (1995) added further momentum to the cultural acceptance of polygonal fighters on home consoles.

Around the same time, Western studios introduced their own polygonal icons like Lara Croft in Tomb Raider and Crash Bandicoot in 1996, though these emerged after Japan had already established the commercial viability and style of 3D characters.

That divergence came down to cultural forces as much as business ones. Japan’s entertainment industry had long embraced mascots and character-driven branding, visible everywhere from consumer packaging to anime. When arcades thrived, games needed to catch attention instantly, and when consoles entered homes, characters needed to become global icons. As a result, Japan introduced polygons to the general public through personalities. Mario, Fox McCloud, and later Sonic’s transition into 3D made the limitations feel charming. Even the rigid movements and angular faces of Resident Evil’s cast in 1996 contributed to tension and mood. Meanwhile, games like Final Fantasy VII (1997) and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998) demonstrated how simplified 3D models could carry emotional storytelling and cinematic atmosphere, cementing character-driven low-poly visuals as the heart of mainstream gaming.

Beyond shaping player expectations, this approach determined the public perception of what 3D graphics could be. A perception that did not fade when technology advanced. As often the case in design, they resurfaced in the 2010s when low-poly visuals returned in indie games and digital illustration, now reinterpreted as a minimalist design choice rather than a hardware limitations.

Not in any way did Japan invent the polygon, and early 3D simulations created in the West were essential to the medium’s development. The technical foundations were international. But Japan defined how poly art would look, feel, and behave when they reached the global mainstream. It gave them personality, cultural relevance, and the ability to connect emotionally with players.

Today’s minimalist game design, geometric illustration, and low-poly branding all trace back to this moment: when Japan placed characters at the center of the 3D transition. The West laid the groundwork for real-time polygon rendering, while Japan turned it into culture, shaping how the world first experienced 3D, and how it continues to interpret simplicity as style. More than three decades later, the echoes of those early choices still define the emotional core of digital characters. The polygon may be universal, but the warmth and personality we once saw in its rough edges reflect a distinctly Japanese legacy.

Before Harajuku, Shoichi Aoki archived the world’s fashion.