Taroman - A Pure Homage to Tokusatsu

Taroman│© NHK

In July 2022, NHK aired Taroman, a ten-part late-night mini-series that posed as a rediscovered 1970s tokusatsu (live-action programs with practical special effects) and paid tribute to the avant-garde artist Taro Okamoto. Blending giant-hero action, malformed kaiju, retro production values and the artist’s rallying cry “Art is Explosion!”, the project created a striking hybrid of pop nostalgia, cultural critique and art-historical homage. Conceived by filmmaker Ryo Fujii, TAROMAN was originally created to support an Okamoto retrospective but swiftly evolved into a full-fledged cultural phenomenon, including a theatrical film released in August 2025.

From Okamoto Retrospective to NHK Late-Night Experiment

The origins of Taroman begin within the walls of the 2022 Osaka comprehensive retrospective of Taro Okamoto’s work. NHK, in partnership with the Okamoto Memorial Foundation, commissioned Taroman as part of the exhibition’s programming, framing it as “rediscovered footage of a 1970s giant-hero show” crafted in the spirit of Okamoto’s art.

Filmmaker Ryo Fujii, known for his visually audacious and conceptually daring projects, conceived Taroman as more than a promotional vehicle: he envisioned it as a “pure glorification of nonsense” (in Okamoto’s words) executed in a 1970s tokusatsu aesthetic. Production deliberately employed retro techniques, such as 4:3 aspect ratio, composite wires, model-sets, and a heavy dose of practical effects. Even the image was “aged” by passing through video decks to simulate archival footage.

Between July 19 and July 30, 2022, NHK broadcast ten five-minute episodes in a deep-night slot. The episodes showcased a tyrannical giant, Taroman, battling bizarre Beasts derived from Okamoto’s works (such as Tower of the Sun), while stylized fan interviews and archival “footage” deepened the mockumentary feel.

What began as an exhibition tie-in soon developed cult momentum. Collectible merchandise, pseudo-documentaries and fan-events proliferated. Taroman had entered the cultural realm as both homage to the Showa-era tokusatsu tradition and extension of Okamoto’s “art for all” philosophy. The shift from display-piece to creative project captured the spirit of the series, playful, art-informed, and unabashedly reckless.

Taroman│© NHK

Recreating 1970s Tokusatsu Aesthetics

If the concept of Taroman emerged from the world of fine art, its execution belonged unmistakably to the universe of 1970s television. Director Ryo Fujii and his team approached the project with the meticulousness of film historians and the irreverence of pop pranksters, crafting what could best be described as an archeological parody. Every visual and sonic element (costume design, monster choreography, editing rhythm, and sound design) was reconstructed to emulate the low-budget exuberance of Japan’s Showa-era tokusatsu television.

The production’s aesthetic compass was guided by Tsuburaya Productions, the legendary studio founded by Ultraman creator Eiji Tsuburaya. Having defined Japan’s live-action science-fiction grammar since the 1960s, Tsuburaya Productions collaborated with NHK to ensure that Taroman’s “fake” show could feel authentically real. Miniature sets were built in the style of Ultraman Leo (1974) or Fireman (1973), complete with toy-scale urban landscapes and visible support wires. Fujii insisted that no digital effects be used, monsters were men in rubber suits, explosions were practical pyrotechnics, and the camera lenses were deliberately soft to mimic the look of 16 mm optical transfers.

The Taroman suit itself, part statue, part superhero, was modeled after Okamoto’s iconic Tower of the Sun, with three faces symbolizing past, present, and future. Designer Shinji Higuchi, a veteran of the industry and co-director of Shin Godzilla (2016), contributed conceptual guidance, ensuring that the hero’s design evoked Okamoto’s surreal biomorphism. The kaiju he battled, dubbed Beasts of Ideas, were not menacing enemies but metaphors for human folly, the Monster of Desire, the Monster of Habit, the Monster of Order. As in Okamoto’s art, chaos was not destruction but liberation.

Stylistically, the show was an exercise in parodic precision. The camera tilts, over-cranked punches, visible seams of latex, all were intentional, each one a wink to the devoted viewer of Ultraman or Spectreman. The editing mimicked analog splicing errors, the narration alternated between melodrama and deadpan absurdity. Taroman does not mock Showa tokusatsu, but re-enacts it with affection.

Equally vital was the soundscape. Composer Ken Arai incorporated period-authentic instrumentation, with surf-rock guitars, distorted trumpets, and synthetic theremins. Dialogue was post-synchronized, slightly off-sync, in deliberate homage to 1970s dubbing techniques. Even the broadcast format, five-minute “episodes” aired late at night, echoed the ritualistic fragmentation of early television culture, when viewers pieced together wonder from static and blur.

Taroman looks, sounds, and moves like a lost tokusatsu relic, yet its purpose was to reflect Okamoto’s conviction that “art must destroy conventional form to reveal new vitality.” By fusing avant-garde art theory with pop-culture pastiche, Fujii and his team resurrected the handmade optimism of the Showa era while reminding contemporary audiences of the joyful absurdity at the heart of creation itself.

The Fictional Fan Culture Around Taroman

When NHK launched Taroman, the show was framed as if it had once aired in the early 1970s, during the golden age of tokusatsu, and had somehow vanished into the fog of collective memory. This clever act of mock-historic invention, a faux archive of posters, behind-the-scenes photos, and grainy “original footage”, blurred the line between reality and nostalgia. What emerged was a full-scale simulation of a cultural memory that never truly existed.

NHK’s promotional materials treated Taroman as a lost series, recently rediscovered in the vaults. Its fictional backstory included references to nonexistent toy lines, forgotten theme songs, and vintage magazines that allegedly covered the “original broadcast.” Viewers were invited to participate in the illusion, sharing “memories” online of watching Taroman as children, despite the fact that none of them could have. This collective act of imagined nostalgia became one of the project’s most brilliant commentaries, a reflection on how media, memory, and myth intertwine in the digital age.

The strategy echoed a long tradition in Japanese popular culture of retrofabrication, the playful creation of fake histories that feel authentic. From Studio Gainax’s mock-documentary Otaku no Video (1991) to the fabricated “lost kaiju films” circulating in fan circles, Japanese media has often explored the pleasure of constructing and consuming invented pasts. Taroman extended this impulse into the institutional realm, with NHK itself playing the role of archivist, historian, and accomplice.

The phenomenon extended beyond the screen. NHK released art books, collectible figurines, and a “retrospective” exhibition featuring the supposed production materials of the original series, displayed with curatorial seriousness. The exhibition catalog included essays by real critics writing about a fictional history, further deepening the conceptual game. Online, the reaction was equally meta. Fans produced fan art of fan nostalgia, creating tributes to a show that had never existed, treating Taroman as both artifact and meme. In pretending to remember Taroman, viewers enacted Okamoto’s credo that art is not bound to truth but to vitality. The fake nostalgia became a form of genuine affection, a demonstration that the spirit of Showa creativity, chaotic and handmade, could still be resurrected through play.

Taroman│© NHK

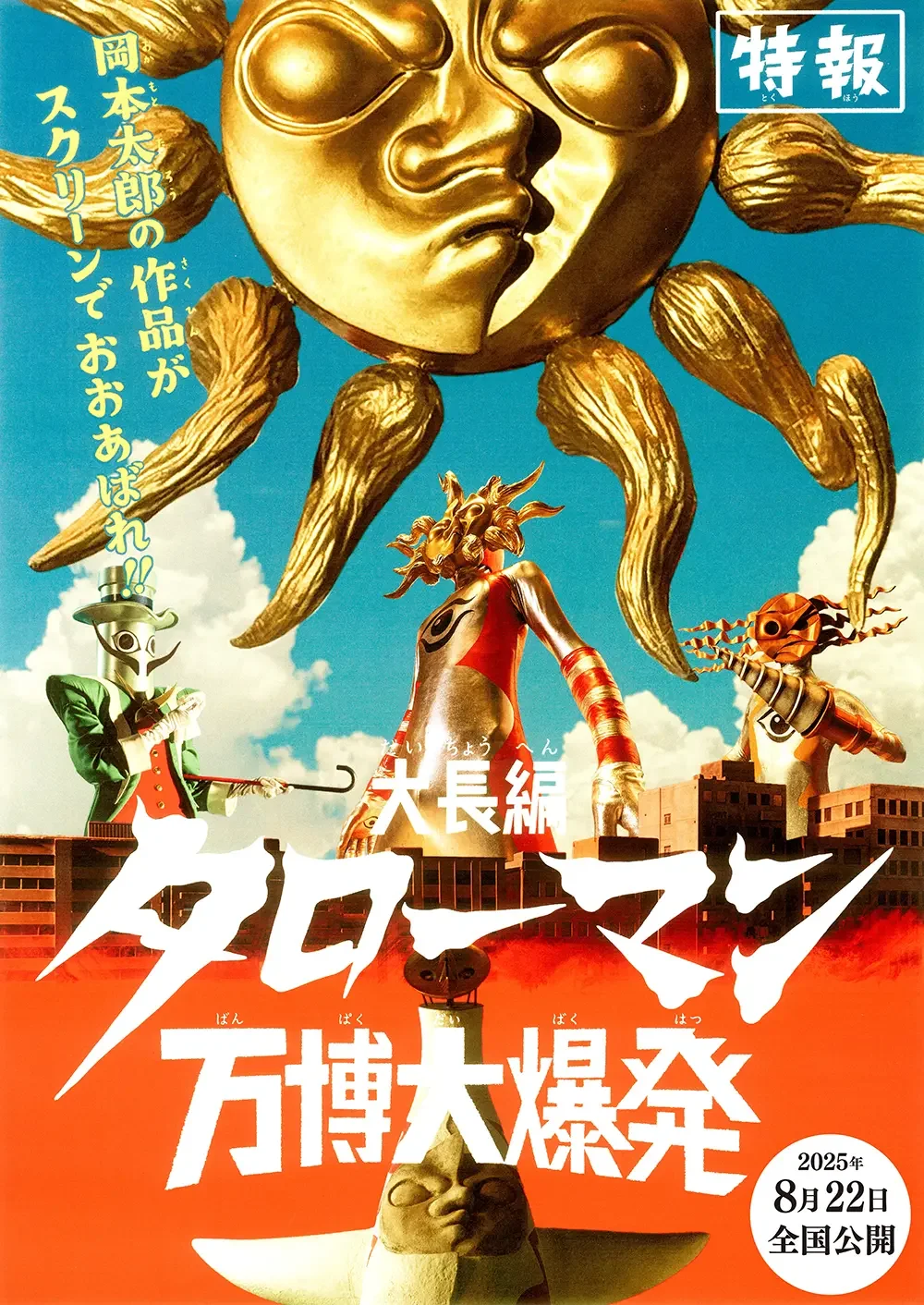

Taroman - Expo Explosion

When NHK and filmmaker Ryo Fujii announced Taroman: Expo Explosion, it was immediately clear that the project would extend far beyond a mere cinematic sequel. Positioned at the crossroads of nostalgia, national identity, and artistic homage, the film reimagines the Taroman mythos through the lens of two pivotal moments in Japan’s modern history: Expo ’70 in Osaka and Expo 2025.

At first glance, the connection might seem straightforward. Both Expos serve as mirrors reflecting Japan’s shifting vision of the future. Expo ’70, organized under the theme “Progress and Harmony for Mankind,” was a dazzling showcase of postwar confidence, a celebration of technology, design, and global connectivity. Its symbol, the Tower of the Sun, designed by Taro Okamoto, remains an enduring icon of that era. More than half a century later, Expo 2025 revisits the same site on Osaka’s Yumeshima Island, this time under the theme “Designing Future Society for Our Lives.” Where Expo ’70 radiated certainty, Expo 2025 is charged with questions about sustainability, coexistence, and the limits of progress.

In Taroman: Expo Explosion, Fujii cleverly collapses these two worlds into one. The film’s premise is gloriously absurd. A monstrous creature from the year 2025 travels back to 1970 to destroy the Expo before it happens, forcing Taroman and the Earth Defense Force to journey into the future to save it. Yet beneath this parody of kaiju eiga (a genre of Japanese cinema that features gigantic creatures), logic lies a surprisingly lucid allegory about time, creativity, and cultural amnesia. Fujii’s approach retains the retro authenticity of the original Taroman series. The production recreates 1970s-style miniatures, practical effects, and analog textures. Yet the setting is unmistakably 2025, a world polished by digital clarity but hollowed by overproduction.

The film’s metaphor is double-edged. Expo ’70 represented an era when Japan believed in the future as a shared destiny, Expo 2025 unfolds in a time when the future feels fragmented, individualized, and uncertain. The film also serves as a meta-commentary on national myth making. Both Expos, in their respective eras, have been instruments of Japan’s self-narration. Expo ’70 dramatized the country’s rebirth from the ashes of war, and Expo 2025 aspires to dramatize its rebirth from demographic decline and ecological crisis. Expo Explosion positions Taroman as the absurd guardian of that continuity, a figure of nonsense charged with preserving meaning.

Ultimately, Taroman: Expo Explosion is less about the hero himself than about what he represents, a bridge between eras, a reminder that even in a hypermodern world, the wild irrationality of art remains essential.

Through its handcrafted miniatures, rubber suits, and surreal moral lessons, Taroman captures the tactile wonder of 1970s tokusatsu while revealing its deeper philosophical undercurrents. By embracing absurdity with sincerity, the series and the film restores the genre’s original sense of play, experimentation, and optimism. It honors the craftsmanship of studios like Tsuburaya Productions, but also the spirit of creators such as Eiji Tsuburaya and Taro Okamoto, whose belief in the power of imagination shaped Japan’s visual identity in the postwar era. In reviving that energy for a new generation, Taroman reawakens the creative pulse that made tokusatsu, and art itself, so explosively alive.

How Mei Semones lets language follow memory.