Hiromix and the Rewriting of Youth

The girl behind the camera

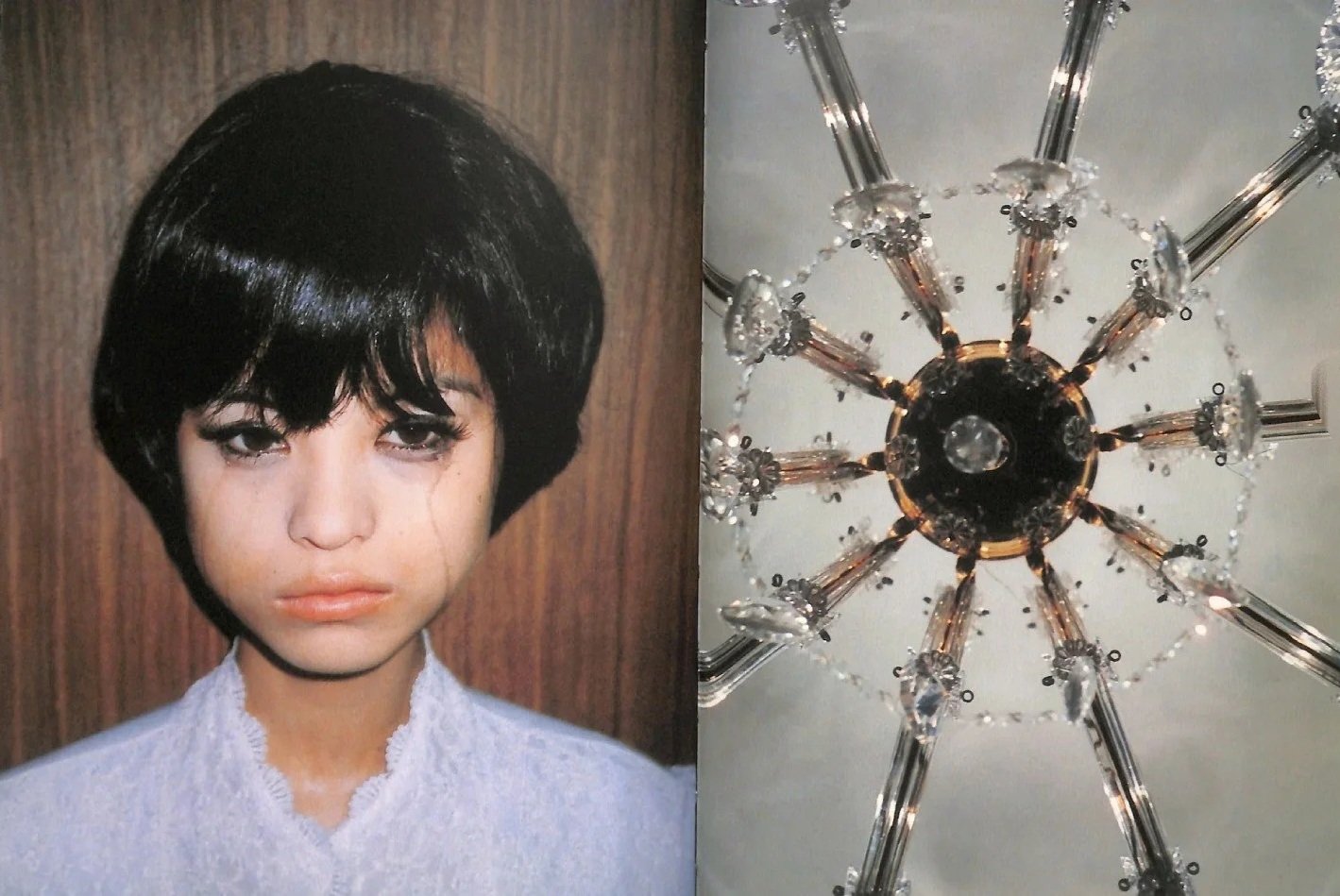

Hiromix Paris ’97-‘98│via Single Eyelid Books│© Hiromix

In the mid‑1990s Tokyo, a new kind of image began to surface. A teenage selfhood burst onto the stage through the lens of a camera-wielding outsider turned icon. What she captured wasn’t particularly new, but it was all in how she framed it. She made a new generation comfortable in observing itself.

Born Hiromi Toshikawa in 1976, Hiromix didn’t set out to be a photographic pioneer. But in 1995, she submitted a photo-zine titled Seventeen Girl Days to the 11th New Cosmos of Photography competition, and won. That moment became a rupture point in Japan’s photographic tradition, one where the male gaze had long monopolized representations of the female form, especially youth. Here was a young woman photographing herself and her world, to simply be.

Into the Interior Life of Hiromix

Hiromix’s early work is often misread as cute or naive. But to call it “snapshot photography” misses the point. Her framing, deliberately off-center, her colors raw, her subjects familiar to the point of invisibility, challenged the very idea of what was worth photographing. Girls Blue (1996), her first major photobook, feels like a personal diary filled with casual city candids of friends and closeups of food. Yet within the nothingness lies the whole presence Hiromix stands for.

This intimate and unspectacular, yet resonating atmosphere, coincided with the rise of “onna no ko shashinka” (girl photographers), a loosely defined movement where women turned cameras on themselves and their peers. The name was coined by Kotaro Iizawa in the mid-90s and included names like Yurie Nagashima. Meaning that Hiromix wasn’t its sole inventor, but she became the movement’s emblem. She harnessed affordable point‑and‑shoot cameras and Purikura kiosks to articulate a new visual grammar, from within the world she depicted.

Japanese Beauty 1997│via Single Eyelid Books│© Hiromix

At just 17, Hiromix submitted a 36‑page zine titled Seventeen Girl Days to the 11th New Cosmos of Photography contest in March 1995, and won Grand Prix, selected by Nobuyoshi Araki himself, launching a massive shift in Japanese visual culture. Seventeen Girl Days unspooled a memory‑journal of half‑eaten breakfasts, blurred faces and indifferent self‑portraits in underwear. Or with Araki’s words: “Girls tend to hold nothing back… they let their feelings rule their actions.”

Hiromix was never just another subcultural figure. She became a mirror that was refracting youth culture back at itself in ways that were both fleeting and foundational. She moved through pop and art like someone who never fully belonged to either. Music videos, films, a solo record titled Hiromix’99, and even a blink-and-you-miss-it cameo in Lost in Translation, her presence started to leave a mark.

The art world noticed. Takashi Murakami brought her into the first Superflat exhibition in 1999, a defining moment in Japan’s strategy to export culture as an aesthetic, not tradition. Thanks to the approach of Hiromix, girlhood was now flattened into something marketable, as privacy got repackaged as public texture. But still, Hiromix’s images remained a kind of visual mutiny against the commercial surface.

Hiromix 1998│via Landslide│© Hiromix

The Diary as a Weapon

What made Hiromix radical as a photographer wasn’t always what she photographed, but how. Where photographers like Araki eroticized vulnerability, Hiromix was living inside it. She embraced the mess and fatigue fashion was glossing over. The development of the diaristic style she pioneered was a way to write herself into a visual language that had long excluded girls like her.

Her books trace that arc. Japanese Beauty (1997) turned the lens outward, to friends, strangers, snapshots of intimacy that still carried her signature emotional undercurrent. Hikari (1997) glowed softer, inward. By Hiromix Works (2000), her imagery matured into a strange hybrid which felt raw yet editorial. That book earned her the Kimura Ihei Award, one of Japan’s highest photography honors, but she never quite settled into the canon. As quickly as she was canonized, she seemed to vanish.

Hiromix’s fingerprints are all over today’s visual culture. Lo-fi emotional storytelling on Instagram. The rise of the self-timer, the tilted frame, the mood over the message. She was doing all of this before algorithms knew what to do with it. But unlike today’s performative self-curation, her work never felt like it was chasing visibility like we see in today’s social media.

As she disappeared into the shadows, Hiromix started publishing drawings, poems, more photo books. But she never tried to cash in on 90s nostalgia, even though she helped define its look. There’s integrity in that. A refusal to become a retro brand of herself. Her work shattered entrenched visual paradigms. Instead of being the object of framing by male photographers, she tipped the balance to the point where Japanese teenage girls began framing themselves, and doing so without aesthetic translation or distance. Her work unlocked expressive agency for young women, giving rise to legions of analog “girl photographers” whose snapshots became a quiet subculture.

Hiromix Works 2000│via Single Eyelid Books│© Hiromix

Core publications

Girls Blue - 1996

A 122‑image photobook drawn from that teenage zine, capturing Tokyo youth culture in peaches, shopping malls, late‑night snacks, friends. Bright, upbeat: “blue” here means fresh and immature, not sad.

Japanese Beauty - 1997

Shifted outward from self‑portraits to diaristic portraits of Japanese models, still lo-fi and diary-like, but documenting other bodies with the same empathetic gaze.

Hikari - 1997

Another personal photodiary, softer and more melodic, less widely circulated but thematically continuous with her diaristic voice.

Hiromix - 1998

Her first Western‑published book, often seen as her introduction to international audiences, feels less retrospective than selective, filtering youth Tokyo into a fragile yet universal portrait.

Hiromix Works - 2000

A heavier retrospective of her music‑magazine assignments (e.g., Rockin’ On Japan), candid celebrity portraits, festival scenes, connecting raw diary photography with rough editorial work. This book earned her the prestigious Kimura Ihei Award in 2000–01.

Other later books include Hiromix Paris ’97‑’98 (2001), Hiromix 01 (2002, poems & drawings), and others, extensions of her diaristic impulse in diverse forms.

Long before the internet made everyone their own curator, Hiromix showed that the ordinary was already enough, that to document your world was, in itself, an act of authorship.

Before Harajuku, Shoichi Aoki archived the world’s fashion.