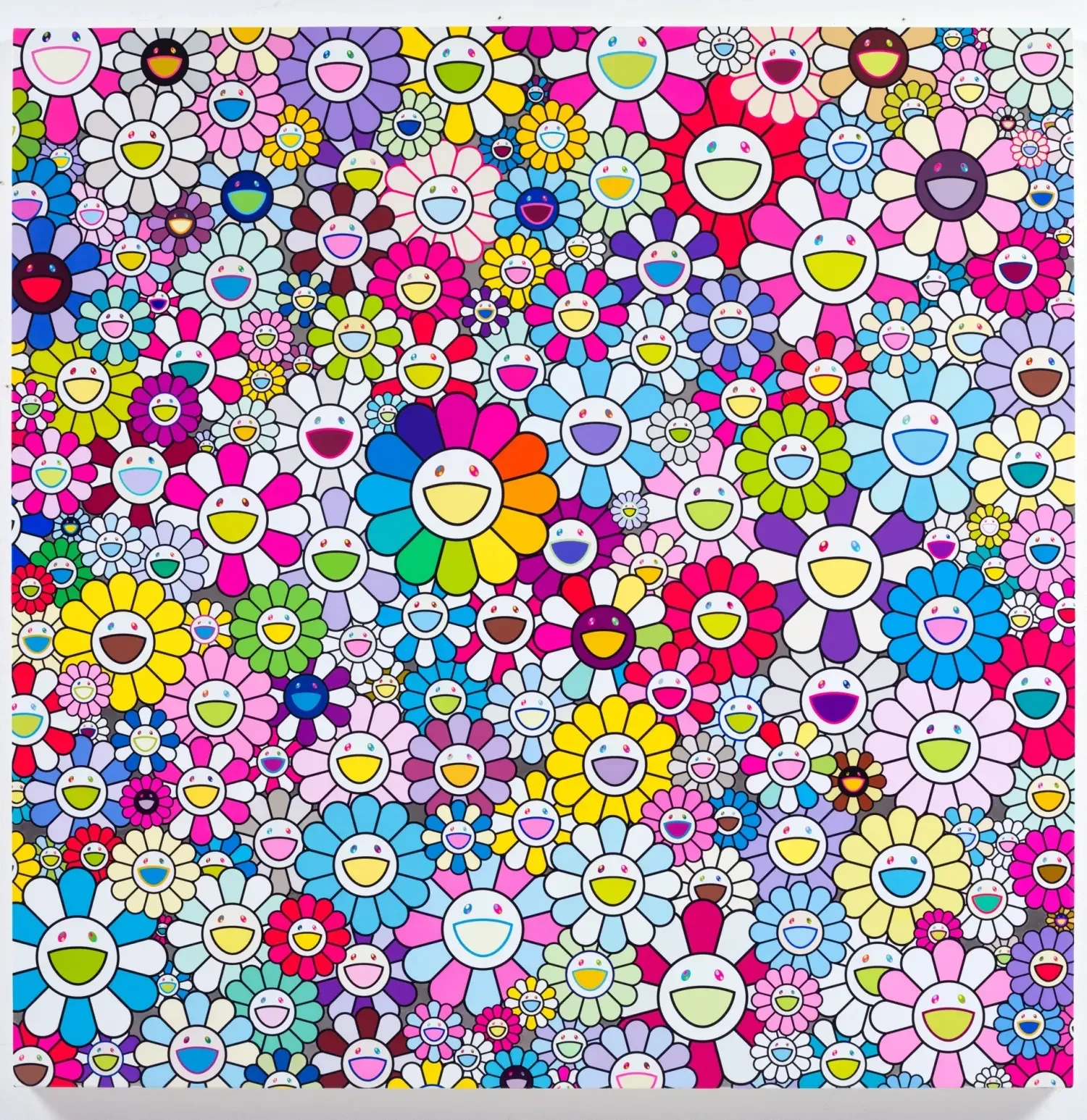

Superflat - Takashi Murakami’s Cultural Theory

Born from a frustration with how Japanese art was understood both inside the country and abroad, Takashi Murakami ignited a quest that would lead him to coin the term Superflat. During the late 1990s, as his work began circulating through Western galleries, Murakami realized that Japan lacked a coherent framework to explain the visual culture that shaped its society. Manga, anime, toys, commercial graphics, and fine art were deeply connected in Japan, yet had no shared language in the global art world. So Murakami looked for an answer: a theory that links Japan’s historical image-making to its postwar identity and to the consumer culture that defines modern life.

The Search for a Japanese Logic of Images

Takashi Murakami’s interest in “flatness” did not begin with anime. It began with his dissatisfaction with Nihonga, Japan’s modern-era attempt to preserve traditional painting methods within a contemporary fine art framework. He studied Nihonga at Tokyo University of the Arts in the 1980s, where the curriculum focused on mineral pigments, gold leaf, washi paper, and compositional techniques derived from pre-modern painting. He admired the technical skill, but he was increasingly frustrated with its static, museum-bound identity. To him, Nihonga functioned as an artificially preserved tradition, frozen in time to satisfy cultural nostalgia rather than express contemporary Japan.

Looking backwards, he found a consistent emphasis on planarity in earlier periods: Edo handscrolls, Kano-school screens, Rimpa painting, and ukiyo-e woodblock prints. Depth and perspective were downplayed in favor of strong outlines, patterned surfaces, and compositions that guide the viewer’s gaze across the picture rather than into it. Murakami’s collaboration with art historian Nobuo Tsuji, especially around the book and exhibition Lineage of Eccentrics, reinforced this view: Tsuji argued that certain Edo painters used unusual cropping, zigzagging compositions, and condensed space to create a distinct, “eccentric” visual rhythm. Murakami came to see this as a historical foundation for Japan’s preference for flat, surface-oriented images.

Another crucial part of Murakami’s thinking concerns how Japan changed after 1945. The shift from militarism to pacifism, the American occupation, and the transformation into an economy driven by consumption reshaped how people related to images. Murakami observed that Japanese postwar society leaned heavily into softness, cuteness, and optimism, partly as a way of avoiding difficult historical memories and partly because the new system rewarded emotional restraint.

This produced a cultural environment where fantasy-driven media played a large role in how people navigated identity, desire, and aspiration. For Murakami, the prevalence of fictional characters with fixed expressions and simplified emotions was not merely an aesthetic choice. It mirrored how society encouraged people to regulate their inner world.

That brings us to the media that filled the screens and shelves of late-20th-century Japan: TV animation, manga, game graphics, figures for otaku collectors. Murakami noticed that these, too, relied on two-dimensional planes, stylized outlines, and symbolic rather than realistic expressions. In his essay A Theory of Super Flat Japanese Art, he explicitly linked Edo-period imagery to modern anime and to the work of key animators, arguing that the compositional strategies of premodern painting persisted in new, mass-produced forms. Anime was not an aesthetic accident; it was the contemporary continuation of an older way of organizing images and directing attention.

For Murakami, this continuity meant that “flatness” could no longer be treated as a mere stylistic quirk. It pointed to a Japanese way of constructing visual space that cut across time, medium, and status. Superflat was created to name this system: a framework that explains why so much of Japan’s art, design, and popular imagery shares a common surface logic, and how that visual flatness is tied to deeper cultural, historical, and social conditions.

© Murakami & Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd.

Defining the Term

Murakami chose the word Superflat not to describe a visual style, but to name a condition that he believed was embedded in Japanese culture. He saw that Japan’s image-making, across many centuries, had favored flattened space, strong outlines, and symbolic rather than realistic representation. But in postwar Japan, this flatness had expanded beyond visual design. It had become a way of organizing culture itself.

His argument was that, in contemporary Japan, the traditional boundaries that once separated cultural categories, fine art, entertainment, advertising, fashion, subculture, and commercial products, had collapsed into the same level. Anime characters could appear on luxury bags. Toys could be displayed in galleries. Murakami himself could sell a sculpture to a museum and a plastic version of it to a convenience store at the same time. In his view, this was not a contradiction, but a defining feature of how Japanese culture operated: a flattening of hierarchies between high and low, original and copy, commercial and artistic.

Murakami saw this flattening not just in distribution, but also in emotion. He argued that contemporary Japanese media compresses emotional expression, using fixed faces, symbolic gestures, and simplified emotional cues. This is not an aesthetic limitation, but a cultural strategy, feelings are not performed through realism, but through codified visual signs. Emotional depth is preserved, but it is delivered through a surface that appears simple. For Murakami, this mirrored a broader social tendency in postwar Japan to regulate expression, and to manage identity through mediated forms such as fictional characters, cute designs, and branded images.

Superflat therefore describes both a visual condition and a cultural attitude.

It names the flatness of pictorial space, but also the flattening of distinctions in how Japan produces, values, and consumes images. It highlights a culture where fiction, commerce, and identity coexist on the same plane, and where surface forms carry psychological and cultural meaning.

Although Superflat began as a theoretical proposition, it gradually became a language through which Japanese art could be read. Artists associated with Murakami, such as Mr., Chiho Aoshima, and Aya Takano, did not imitate his style, but shared his interest in surface-driven imagery, youth culture, and the blurred area between desire, fantasy, and consumer goods. Curators began using Superflat to explain how painting, anime, fashion, advertising, and collectible objects could operate within the same cultural ecosystem.

Murakami’s exhibitions, particularly Superflat (2000) and Little Boy (2005), introduced the term into contemporary art discourse as more than a description of visual flatness. They positioned it as a reading of Japan’s cultural condition: a way to understand how its visual language evolved and why surface imagery carries so much meaning in a society shaped by modern consumption, historical memory, and mediated identity.

In this sense, Superflat is not a stylistic guideline or an aesthetic label. It is Murakami’s attempt to define a logic: a theory that connects Japan’s visual past with its mass-produced present, and a lens through which the structure of Japanese cultural expression can be understood.

Wenders wanders a city racing forward, searching for Ozu’s stillness.